My wife and I have to shell out a lot of money to pay off student loans, because in breaking news that should surprise absolutely nobody: medical school is really, really expensive. I won't give you the precise dollar figure of our monthly payments, but I will say that it is by far the biggest line item in our monthly budget, more than rent or car payments or groceries. Even though we are a two-income household, we live rather modestly.

On a similar sort of scale, I have friends and colleagues who took on student loans for seminary that are, relative to their salary, quite massive. Tuition at a name-brand divinity school like the University of Chicago currently costs $10,524 per quarter for M.Div. students--which computes to $31,572 per year and $94,716 total if you complete the degree in the expected three years for full-time students.

$94,716. For a job whose median annual salary (as of May 2014) is a hair under $44,000.

Now, I realize: not every seminary is as expensive as Chiago (mine wasn't). And many students do receive extensive financial aid from their seminaries (I did). But especially as far as the latter is concerned, I *know* that I am one of the lucky ones.

Because really, for as long as seminaries and divinity schools continue to be a part of the higher education tuition bubble (which has to burst at sometime, because there is just no way something that grows 400% in cost over just a couple of decades can remain sustainable), one of two things will eventually happen: either a seminary education will become cost-prohibitive, or, churches are going to have to start paying their pastors more in order to justify the outlay of capital to afford a seminary education to begin with.

The implications of the first are almost too dire to contemplate. I rag on seminary education a lot, but the truth is, without it, the church would be the crew of a ship up the creek without a paddle. Seminary doesn't just teach the academic heavy lifting of Biblical exegesis, esoteric theology, and history-that-nobody-cares-about-but-your-professor, it also teaches ethics, emergency pastoral care and counseling, and other such skills that can legitimately be the difference between uplifting someone emotionally or spiritually and destroying them.

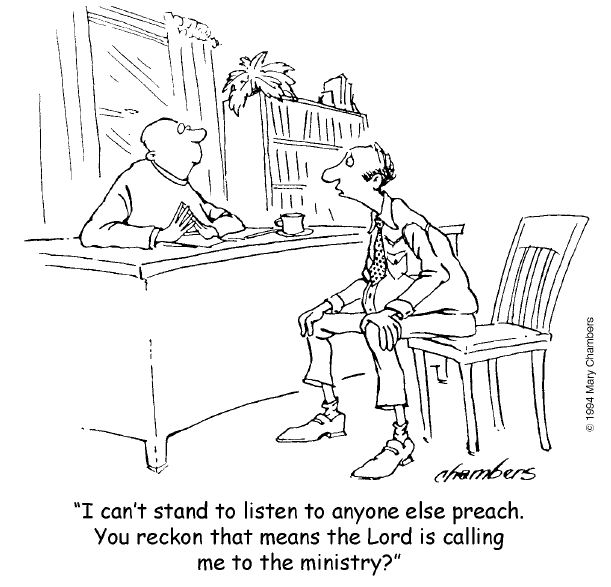

The second possibility, though, is just as difficult as the first one is dire. Congregations, regions, denominations--across the board, churches in America are not just spilling red ink, they are hemorrhaging it. So the argument goes, why should Christians go to seminary to become pastors when the congregations that will employ them after they graduate cannot afford to pay them in such a way as to make the education they received in order to have the job be worthwhile?

In the face of these realities, lots of talking heads have said, "Well, the new future for clergy is to be bivocational," essentially, to do ministry part time and something else part time. Or, to split one's time ministering between two churches. While such a system might work in a more socialist country where access to the health care system isn't predicated on having insurance through one's employer, we are light years away from bivocational ministry being a viable alternative to honor the monetary sacrifice of the practitioners of a vocation that is already physically and mentally unhealthy enough as it is.

Moreover, and I quote a colleague of mine (who shall remain nameless) when they got moved to part time by their congregation: "There's no such thing as part time ministry, only part time wages." Part of parish ministry is a bit like being on a retainer--you're retained to be able to respond 24/7 to crises and emergencies that require a pastoral presence. That part of your job description becomes exponentially more difficult if you cannot respond because you're out of town on account of your other job that actually pays the bills.

Doing pastoral ministry in one's free time is likewise difficult to imagine doing. If I tried to shoehorn my sermon preparation and writing, my administrative work, and my pastoral care into my evenings and days off, my wife and I would never see each other. Coming back with these sorts of expectations is especially unhelpful to younger clergy who are wanting to start families or who have kids at home as much as it is unhelpful to older clergy who may have grandchildren they want to visit or are responsible for sometimes babysitting.

Meanwhile, consolidation or merging isn't always an option, especially for more rural parishes like mine, and even then, congregations are still facing the immediate consequence of likely having to lay off at least some employees (after all, one church usually doesn't need two receptionists).

Which is why congregations--and the seminaries that provide them with trained, educated pastors--need to be the best possible stewards of their resources...because a pastor who makes only $44,000 a year to provide you with quality spiritual care shouldn't be a luxury item for anyone. The problem is, an untrained, unprepared pastor who makes far less has a greater possibility of doing more harm than good spiritually.

I imagine people who see my view here critically will respond with, "You knew what you were signing up for." Yeah, that's a fair point, I did. I know that if God wanted me to be wealthy, God would have called me to the LSATs and the bar exam, not the GREs and the ordination interviews (although even lawyers aren't making anywhere near the scratch they used to). I'm not expecting to be paid more than a middle-class wage during my entire career.

But I'm also not wrong for expecting my colleagues in ministry who work long hours, donate their own time and money (seriously, in what other occupation do you automatically give 10% of your salary right back to your employer?), and never really have the option of punching out on the time clock to make enough to live on and to pay back their debts on.

Because while those of us in more traditional churches may still sing "Jesus Paid It All" as one of our Sunday worship tunes, the world, unlike many of our churches, has moved on and is charging its seminarians a proverbial arm and a leg in order to hone the skillset our churches need and require of us.

We need to be able to adjust to this new and, honestly, hardhearted world if we are to support the amazing things that the thousands of enthusiastic, Spirit-filled, God-driven pastors across the country are doing for their respective churches.

My hope and prayer is that we do.

Longview, Washington

February 9, 2016

Image courtesy of gci.org

No comments:

Post a Comment