I'm an 11 year old wizard, and my letter from Hogwarts just arrived.

If by "11 year old wizard," you mean "29 year old pastor," and by "Hogwarts," you mean "Seattle University."

This is one of those announcements of the greatest kind. Presuming the pieces of the financial aid puzzle all fall into place, I will be matriculating into the Doctor of Ministry program of Seattle University's School of Theology and Ministry, beginning this July.

This will not take me away much from my current ministry; the D.Min. (pronounced, basically, "demon," an irony which was most certainly not lost on my church's board of directors) has for decades now been a degree designed specifically for working pastors because it is, like its M.Div. sibling, a practical degree. Or, at least, it is meant to be...the M.Div. wasn't always for me (see my most immediate previous post).

But I'm hoping that this D.Min. program (and I chose it in part because of its strength and focus in the area of developing pastoral leadership skills) will remedy some of that, a week or two of intensive classes at a time, over the course of the next three or four years.

It varies dramatically from the Ph.D. in that way. The D.Min. is a degree meant to be completed on a part time schedule, and so it lacks some of the components of a Ph.D. I don't have to take comprehensive exams, for one. And our dissertation, like a Ph.D.'s, is hyper focused on one particular thing, but that thing in our case tends to be our parishes, or a particular mechanism of our denominations, or the like, whereas the Ph.D.'s is an original academic contribution to their field (which, when that field is as heavily researched as, say, Biblical Studies, makes the effort of trying to come up with something both original and academically sound to say seem particularly hellish).

Which means that the D.Min. suffers from a diminished reputation in some (mostly academic) circles. Which is fine, really; I'm not at all interested in being called "doctor," except maybe by my anesthesiologist wife for the laughs (I already have plans to order address labels as "Real Dr. and Fake Dr. Atcheson").

And had I wanted to teach at a university or seminary full time, I would get a Ph.D., but as it is, those professorships are almost ridiculously few and far between as those very same seminaries and universities continue to move away from the model of tenure track professors to hiring more and more non tenure track instructors and part time adjuncts for obscenely low pay (I'm not kidding, either. I may make less than a public schoolteacher, but a lot of college adjuncts have the Ph.D. that I don't and never will, and their average salary is literally half my modest wages. What our postsecondary school system is doing to its adjuncts is criminal in every sense of the term).

But I digress. Adjunct pay is a soapbox for another post. All of this is to say, I don't need a Ph.D. for the work I love doing, so I won't try to pursue one. But I also knew when I graduated seminary that I wasn't done learning; in fact, I withdrew from Santa Clara University's Jesuit School of Theology one week prior to classes starting for their Master of Theology degree in order to come to the congregation I am at now.

So I suppose that I am trading one Jesuit school for another, but hey, I had to read Ignatius of Loyola in college and enjoyed him, so why not? I'm ready to continue learning. And hopefully, I always will be, for God always has something new to teach me. Of that I am certain.

Now, if you'll excuse me, I'm off to Ollivander's to buy myself a wand.

Yours in Christ,

Eric

"I too decided to write an orderly account for you, dear Theophilus, so that you may know the truth..." -Luke 1:3-4. A collection of sermons, columns, and other semi-orderly thoughts on life, faith, and the mission of God's church from a millennial pastor.

Thursday, January 29, 2015

Tuesday, January 27, 2015

Annual General Meetings: Why Sometimes I Wish I had Scrooge McDuck as a Congregant

Look.

I get it.

Love of money is the root of all sorts of evil. Jesus Himself said it.

I don't think I love money. But I know I need it. My landlord won't accept free Bible lessons to pay the rent.

So I need money to live. We all do.

Including churches. Which means we have to budget that money in order to be accountable and transparent to the people who generously give us their money as sacrificial offerings to God.

So, like a lot of congregations, we passed a yearly budget at our annual general meeting yesterday. And, like a lot of congregations, our budget for the year has a pretty big deficit to it. I won't say how big, but suffice it to say you could fit a camel through it easier than through the eye of a needle.

This year's budget, like the past three, included no raise in my own pay either, if for no other reason than I know full well that my loving little congregation cannot afford it. We live in a town that has been beaten senseless by the loss of manufacturing jobs over the past two decades, and now the majority of us here are suffering. And they look the church for help.

But it means that our church is suffering, too. When I came here in 2011, I didn't realize just how much deferred maintenance I was inheriting, or how desperate and acute need existed in the neighborhood for basic necessities like heat and water. You wouldn't think it to look at the stretch of street my church is on, but everyone here was, and is, hurting.

And I am rather entirely unequipped to change that reality. Which means maybe I am paid what I should be paid, which isn't a ton, but it also leads to this particular reality of many an annual general meeting elsewhere, which the Presbyterian pastor/writer/speaker, and a patron saint of the Theophilus Project, Carol Howard Merrit captures fantastically:

The personnel chair gets up and informs the gathering that the pastor is already at the minimum salary, and there is no way to cut the salary any more. Unless, of course, the pastor goes to part time, for instance. The pastor begins looking to see if there is an insurrection brewing.

The budget passes, with a reluctant majority. The pastor sweats as the whispers continue. No one knows how they’re going to keep their pastor. The pastor becomes very anxious, but doesn't know how to respond, because the minister has not done anything wrong. There has even been growth and vitality in the last years. But that still can't make up for the last couple decades of decline or keep people alive. The pastor has mouths to feed and loans to pay. The message is clear. The church will not be able to afford their leadership for long. It's hard to focus on ministry, so the pastor begins putting energy and effort into looking for another call.

The problem is that there are so many churches in this same position, a call to a stable congregation is becoming more rare. There are some really cushy positions. In fact, the income inequities are quite startling—even on the same church staff. But those positions are getting fewer.

So what do we do? Do we go the way of attrition? Do we allow pastors to be starved out, until we all get jobs as baristas? Should churches all hire lay pastors? Then what’s the role of our seminaries? Will we close them down? What about our historic commitment to theological education? Do we just turn our backs on our historic commitments? Is there another way out of this?

Now, this isn't quite my own situation: I'm not looking for another call, and there is no insurrection brewing. But the "there has been growth and vitality in the last years but that still can't make up for the last couple decades of decline or keep people alive" bit? 100% hits the nail on the head. As does the reality that I don't know for how much longer my dear congregation can afford me at my (modest) full-time wages.

This isn't to air dirty laundry because I don't think there is any shame in this, or, at least, there shouldn't be. It isn't like my congregation is a kid who has blown its allowance on Funyuns and Pokemon cards. It's that the church was built to be a much bigger thing than it currently is, and a much wealthier thing than it currently is, and that people who through no fault of their own have lost out on higher-paying jobs or on any job altogether cannot afford this church as it currently exists.

It's not that we don't have Scrooge McDucks anymore, people who could obsessively tuck away their savings. It's that we have so, so many folks who have nothing to tuck away at all.

And we don't know what to do about that. Carol wrote that church planting wasn't even mentioned in her seminary education, not even one class on starting a new church; I would go one further and say that fundraising, property stewardship, and the other nuts-and-bolts types of things that are inherent in running any nonprofit organization, including a church, are not mentioned either, much less taught. For instance, I was taught nothing about online giving and stewardship, even though increasing amounts of commerce and charity take place online, and even though many, many young people (myself included) do not regularly carry cash or checks on them. But we are still teaching our pastors from an outdated perspective that is firmly planted in the era of collection plates and donation boxes.

I talked about this some with my regional minister today, even. I've said it before here, but I'll say it again: I can tell you about the theology of rutabagas during the Council of Nicea, and maybe even come up with a haiku about it, but I went into this gig completely ill-equipped for the practicalities that I imagine the vast majority of solo pastors like me face.

And it is genuinely difficult for me to not feel resentful of that sometimes. I spent three years and thousands of dollars on that education. Not only are we not paying our pastors adequately, we are not educating them adequately. We are asking them to give years of their lives and incredible sacrifices of their resources for a credential that falls short.

Which is why I'm not sure the way that Carol is that the answer lies within the resources possessed by our denominational bodies, because they are the ones who are (usually) the ones providing the inadequate educations our seminaries are offering. And maybe that is the bottom-up-rather-than-top-down Disciple of Christ denominational partisan in me talking. But I think the answer is going to have to come from us. Our denominational bodies may have the funds, but our regions don't necessarily--just last year, the neighboring Disciples region of Southern Idaho dissolved and was absorbed by several neighboring regions because, in part, of an acute lack of resources and of a lack of a base of congregations to draw resources from.

In other words, if our congregations cannot help prop up our denominational infrastructures, maybe our denominational bodies are going to go the same way that we are. As are our seminaries.

I said in my sermon yesterday that perhaps we get the prayer we deserve. Well, maybe we get the levels of giving that we deserve as well.

Except that increasingly, those levels of giving do not allow for us to abide by Paul's dictum that those who preach the Gospel should earn their living by the Gospel.

And that problem is always going to grow if our individual congregations, pastors, and seminaries do not change, regardless of how much Scrooge McDuck gold our denominations are sitting on. That I'm willing to bet on.

But not too much, because I still can't offer my landlord free Bible lessons to pay my rent.

Yours in Christ,

Eric

(Scrooge McDuck image source: Gawker Media)

I get it.

Love of money is the root of all sorts of evil. Jesus Himself said it.

I don't think I love money. But I know I need it. My landlord won't accept free Bible lessons to pay the rent.

So I need money to live. We all do.

Including churches. Which means we have to budget that money in order to be accountable and transparent to the people who generously give us their money as sacrificial offerings to God.

So, like a lot of congregations, we passed a yearly budget at our annual general meeting yesterday. And, like a lot of congregations, our budget for the year has a pretty big deficit to it. I won't say how big, but suffice it to say you could fit a camel through it easier than through the eye of a needle.

This year's budget, like the past three, included no raise in my own pay either, if for no other reason than I know full well that my loving little congregation cannot afford it. We live in a town that has been beaten senseless by the loss of manufacturing jobs over the past two decades, and now the majority of us here are suffering. And they look the church for help.

But it means that our church is suffering, too. When I came here in 2011, I didn't realize just how much deferred maintenance I was inheriting, or how desperate and acute need existed in the neighborhood for basic necessities like heat and water. You wouldn't think it to look at the stretch of street my church is on, but everyone here was, and is, hurting.

And I am rather entirely unequipped to change that reality. Which means maybe I am paid what I should be paid, which isn't a ton, but it also leads to this particular reality of many an annual general meeting elsewhere, which the Presbyterian pastor/writer/speaker, and a patron saint of the Theophilus Project, Carol Howard Merrit captures fantastically:

The personnel chair gets up and informs the gathering that the pastor is already at the minimum salary, and there is no way to cut the salary any more. Unless, of course, the pastor goes to part time, for instance. The pastor begins looking to see if there is an insurrection brewing.

The budget passes, with a reluctant majority. The pastor sweats as the whispers continue. No one knows how they’re going to keep their pastor. The pastor becomes very anxious, but doesn't know how to respond, because the minister has not done anything wrong. There has even been growth and vitality in the last years. But that still can't make up for the last couple decades of decline or keep people alive. The pastor has mouths to feed and loans to pay. The message is clear. The church will not be able to afford their leadership for long. It's hard to focus on ministry, so the pastor begins putting energy and effort into looking for another call.

The problem is that there are so many churches in this same position, a call to a stable congregation is becoming more rare. There are some really cushy positions. In fact, the income inequities are quite startling—even on the same church staff. But those positions are getting fewer.

So what do we do? Do we go the way of attrition? Do we allow pastors to be starved out, until we all get jobs as baristas? Should churches all hire lay pastors? Then what’s the role of our seminaries? Will we close them down? What about our historic commitment to theological education? Do we just turn our backs on our historic commitments? Is there another way out of this?

Now, this isn't quite my own situation: I'm not looking for another call, and there is no insurrection brewing. But the "there has been growth and vitality in the last years but that still can't make up for the last couple decades of decline or keep people alive" bit? 100% hits the nail on the head. As does the reality that I don't know for how much longer my dear congregation can afford me at my (modest) full-time wages.

This isn't to air dirty laundry because I don't think there is any shame in this, or, at least, there shouldn't be. It isn't like my congregation is a kid who has blown its allowance on Funyuns and Pokemon cards. It's that the church was built to be a much bigger thing than it currently is, and a much wealthier thing than it currently is, and that people who through no fault of their own have lost out on higher-paying jobs or on any job altogether cannot afford this church as it currently exists.

It's not that we don't have Scrooge McDucks anymore, people who could obsessively tuck away their savings. It's that we have so, so many folks who have nothing to tuck away at all.

And we don't know what to do about that. Carol wrote that church planting wasn't even mentioned in her seminary education, not even one class on starting a new church; I would go one further and say that fundraising, property stewardship, and the other nuts-and-bolts types of things that are inherent in running any nonprofit organization, including a church, are not mentioned either, much less taught. For instance, I was taught nothing about online giving and stewardship, even though increasing amounts of commerce and charity take place online, and even though many, many young people (myself included) do not regularly carry cash or checks on them. But we are still teaching our pastors from an outdated perspective that is firmly planted in the era of collection plates and donation boxes.

I talked about this some with my regional minister today, even. I've said it before here, but I'll say it again: I can tell you about the theology of rutabagas during the Council of Nicea, and maybe even come up with a haiku about it, but I went into this gig completely ill-equipped for the practicalities that I imagine the vast majority of solo pastors like me face.

And it is genuinely difficult for me to not feel resentful of that sometimes. I spent three years and thousands of dollars on that education. Not only are we not paying our pastors adequately, we are not educating them adequately. We are asking them to give years of their lives and incredible sacrifices of their resources for a credential that falls short.

Which is why I'm not sure the way that Carol is that the answer lies within the resources possessed by our denominational bodies, because they are the ones who are (usually) the ones providing the inadequate educations our seminaries are offering. And maybe that is the bottom-up-rather-than-top-down Disciple of Christ denominational partisan in me talking. But I think the answer is going to have to come from us. Our denominational bodies may have the funds, but our regions don't necessarily--just last year, the neighboring Disciples region of Southern Idaho dissolved and was absorbed by several neighboring regions because, in part, of an acute lack of resources and of a lack of a base of congregations to draw resources from.

In other words, if our congregations cannot help prop up our denominational infrastructures, maybe our denominational bodies are going to go the same way that we are. As are our seminaries.

I said in my sermon yesterday that perhaps we get the prayer we deserve. Well, maybe we get the levels of giving that we deserve as well.

Except that increasingly, those levels of giving do not allow for us to abide by Paul's dictum that those who preach the Gospel should earn their living by the Gospel.

And that problem is always going to grow if our individual congregations, pastors, and seminaries do not change, regardless of how much Scrooge McDuck gold our denominations are sitting on. That I'm willing to bet on.

But not too much, because I still can't offer my landlord free Bible lessons to pay my rent.

Yours in Christ,

Eric

(Scrooge McDuck image source: Gawker Media)

Sunday, January 25, 2015

This Week's Sermon: "The Mountaintop"

Matthew 6:7-15

7 “When you pray, don’t pour out a flood of empty words, as the Gentiles do. They think that by saying many words they’ll be heard. 8 Don’t be like them, because your Father knows what you need before you ask. 9 Pray like this:

Our Father who is in heaven, uphold the holiness of your name. 10 Bring in your kingdom so that your will is done on earth as it’s done in heaven. 11 Give us the bread we need for today. 12 Forgive us for the ways we have wronged you, just as we also forgive those who have wronged us. 13 And don’t lead us into temptation, but rescue us from the evil one.

14 “If you forgive others their sins, your heavenly Father will also forgive you. 15 But if you don’t forgive others, neither will your Father forgive your sins." (Common English Bible)

7 “When you pray, don’t pour out a flood of empty words, as the Gentiles do. They think that by saying many words they’ll be heard. 8 Don’t be like them, because your Father knows what you need before you ask. 9 Pray like this:

Our Father who is in heaven, uphold the holiness of your name. 10 Bring in your kingdom so that your will is done on earth as it’s done in heaven. 11 Give us the bread we need for today. 12 Forgive us for the ways we have wronged you, just as we also forgive those who have wronged us. 13 And don’t lead us into temptation, but rescue us from the evil one.

14 “If you forgive others their sins, your heavenly Father will also forgive you. 15 But if you don’t forgive others, neither will your Father forgive your sins." (Common English Bible)

“The

Mountaintop,” Matthew 6:7-15

“As One

Having Authority: Sermons that Changed the World,” Week Two

The words are about as desperate as they sound

out of context as in context: “Help!

Help! I’ll become a monk!”

They are the words that a law student uttered as

he was riding home on horseback in the midst of a thunderstorm when a bolt of

lightning struck the ground right next to him.

Unlike most of us who probably have bargained with God at some point in

the throes of shock and fear, the law student kept his word and became an

Augustinian monk. His father was

furious—to him, it was as though his errant son was taking his highly-regarded

legal education and setting it on fire—but there was no stopping this young

chap.

And thus was created Martin Luther, the religious

teacher and reformer and forefather of Protestant Christianity, rather than

Martin Luther, the ambulance-chasing lawyer (or whatever the equivalent of

ambulances were back then…stretcher-bearer chaser? Say that ten times fast).

All because he saw as an authentic prayer what we

might have seen merely as an utterance of panic. Where we might have seen only a want to

survive, Luther saw the genuine article, a spiritual calling. And that is what prayer can do. It is, truthfully, what it should do. It should pave the way for those higher

callings we are meant to engage in, those high callings to social justice and

care and compassion that we talked about last week. Prayer fuels all of that, and so it is

appropriate that we turn today to a sermon whose core is all about prayer: the

Sermon on the Mount.

This is a new sermon series to go along with the

new year, and it will take us all the way up to Ash Wednesday, which marks the

beginning of the church season of Lent.

For a while now, I have wanted to talk to all of you about the meaning

and significance of preaching, and this series allows me to do exactly

that. The title for this series comes

from the assembled crowd’s reaction to Jesus’s Sermon on the Mount, where

Matthew says that they were astounded that He taught them as “one having

authority,” rather than one of their temple authorities. So…how do we teach one another as one having

authority? That’s what we’ll be working

on together, and each week for the next five weeks, we will be talking about

one of the many significant sermons that are given in the New Testament: the

Sermon on the Mount, Peter’s Pentecost sermon, Stephen’s farewell speech before

his martyrdom, and Paul’s address to the Areopagus. We began this series by looking at Jesus’s

first sermon in His ministry as documented by Luke in his Gospel, and it was

appropriate that we did so on the weekend of Martin Luther King, Jr. Day

because this resounding call for justice from Isaiah 61 that Jesus preaches on

was King’s message as well, and today, we move, as I said, to the Sermon on the

Mount, which Matthew holds as Jesus’s inaugural sermon rather than the sermon

on Isaiah 61 in the Nazareth synagogue which Luke documents.

Nevertheless, whichever one came first, the

chicken sermon or the egg sermon (so to speak), both messages were profoundly

important for setting the tone for everything else that was to follow in

Jesus’s earthly ministry. They both

encapsulate, in their own ways, what this whole Christianity thing is all about—or,

at least, what it was meant to be about and should still be about.

Now, first things first—does it matter at all

where Jesus is preaching the Sermon on the Mount?

Absolutely, it does. It evokes the image of Moses, ascending Mount

Sinai to receive the law (beginning with the Ten Commandments) from God, and so

in turn does Jesus ascend to interpret the law that Moses once received. Not only that, though, but as Father Albert,

my favorite Bible professor from seminary taught, the Sermon on the Mount

itself is shaped like a mountain—perfectly symmetrical from a beginning-and-end

perspective, with each end (chapter 5 and chapter 7 of Matthew) climbing to a

particular point as the sermon’s peak.

And that peak is this passage wherein Jesus teaches us the Lord’s

Prayer, atop the mountain.

This mountaintop, ultimately, is all about trying

to get closer to God. It is why the

primeval ancients built the Tower of Babel in Genesis 11; since they believed

that God lived in the skies (personally, I believe God lives in maple syrup,

but nobody else seems to subscribe to that extremely well-grounded hypothesis),

then they would try to reach the skies themselves and thus be close to God and

be like gods themselves. That didn’t

turn out so well for them.

The same sort of thing, in fact, happens while

Moses is up on Sinai, which is what—as I just said—Jesus is emulating

here. When Moses comes down from the

mountaintop with the tablets inscribed with the Ten Commandments (or the

Fifteen Commandments, if you believe Mel Brooks in his “History of the World,

Part I”), he discovers that the Israelites have taken to worshipping the golden

calf, because that puts God (or rather, their idol of a god) closer to them and

in their midst, and Moses smashes the tablets in fury. This doesn’t turn out so well, either.

But hey, third time’s a charm, right? Except that the Lord’s Prayer isn’t really a

third time, it’s a first time, a first attempt; there isn’t anything else quite

like it. It’s unique, a one-off. Certainly, there are other prayers and

identical sentiments expressed elsewhere at varying points within Scripture,

but only here are they encapsulated so simply and so elegantly and, ultimately,

so accessibly into a single prayer that it can be learned and recited even as a

young child.

And really, that is what prayer is for, in the

end. It is to be accessible to us, and

for us to begin to pick up on as early as possible, because it is what fuels

everything else. All the other stuff I

talked about last week: working for equality for all people, striving for

social justice, performing individual acts of charity and goodness, all of

those, ALL of them, are fueled ultimately by prayer, by an act of us trying to

bring ourselves closer to God as a spiritual practice. Prayer enables all of that.

It does this because prayer, at its core form,

though it often comes down, as Christian writer Anne Lamott says, to either

“Please, please please,” or “Thank you, thank you, thank you,” prayer at its

core form is an expression of faith in a being mightier and greater and far

more encompassing than our little feeble selves could ever be. It is the reversal of the sentiment behind

the creation of the Tower of Babel, or of the golden calf at Sinai: it is the

ultimate concession that we are not gods, that we will never be as God is, and

for us to see and recognize and appreciate God’s movement in our lives, we need

to be able to pray to God about it first.

That is something that I have, if I am completely

honest with you, often struggled with.

Prayer sometimes feels like it saps energy from me rather than giving me

energy, and as a result, I end up slowly chiseling away at my own stores of

faith. It is a terrible condition to

have when your job means that you are (understandably) expected to pray on

command at family dinners and the like, and when I do find myself in a moment

when I do not know how to pray or what to pray for, I have to remember that

Jesus already taught me how to pray and what to pray for.

So I try to make whatever prayer I am saying

within the same contours of the Lord’s Prayer.

And it seems to work, if I simply try to ask God

for the things Jesus instructs us to ask God for, the things that Jesus says it

is okay to ask God for. My mom just

posted this article to her Facebook page this morning, so this is a late

insert, but what the hell: apparently, 1 of 4 Americans think that God will

have a direct hand in determining who wins the Super Bowl. I guess what is reassuring is that the other

3 of 4 folks don’t, but still. I get

that we all want the Seahawks to go back-to-back here, but “give us this day

another Super Bowl title” isn’t exactly a faithful translation of Matthew 6:11.

But if this is what we expect of God and of

divine intervention by God, maybe we get the prayer we deserve. I know I just self-flagellated publicly over

my own prayer shortcomings, so I am a proud hypocrite here, but I feel this

every time I hear a Christian—even a pastor—pray a prayer that sounds like,

“Father, we just want to just say to you, Father, just that you, Father, just,

just, just.” It’s such an insidious

thing that the perennially funny Christian writer Jon Acuff satirized it on his

humor blog, “Stuff Christians Like.”

Me, I honestly kind of want to put my fingers in

my ears when I hear that particular prayer.

That’s not a prayer, that’s what Jesus calls babbling on and on.

So maybe we get the prayer we deserve. But we shouldn’t. Or, rather, we shouldn’t settle for that. Because God sent Jesus with a message of how

to pray as we ought, to pray a prayer worthy of our faith., of a faith that,

like these sermons, can still change the world.

So let us settle for that instead. Let us settle for praying as Jesus taught

us. Nothing more, nothing less.

Because in the end, there truly is nothing less

than that.

Thanks be to God.

Amen.

Rev. Eric Atcheson

Longview, Washington

January 25, 2015

(original image via speakupmovement.org)

Thursday, January 22, 2015

When a Mover of Your Life Dies

Marcus Borg, the Bible scholar loved and disdained in equal measure across Christianity's spectrum, died yesterday at the age of 72.

When I first heard the news, I posted this to my Facebook page:

I just read about Bible scholar Marcus Borg passing away yesterday. I didn't agree with everything he said, especially about Easter and the nature of the Resurrection, but his book "The Last Week" that he co-wrote with John Dominic Crossan was (is) one of those "it changed my life" books, and months before he died, I had already planned to use that book as the template for my Lenten sermon series this year, to begin on Sunday, February 22. That sermon series takes on an added dimension for me with his, as he himself put it, "dying into God."

Go with God, Dr. Borg. Thanks for everything.

In The Last Week, Borg and Crossan, even though they argue for setting the factual nature of the Resurrection aside in order to approach it as a parable (something I never understood, because they are writing primarily about Mark's Gospel, and Mark's account of the Resurrection is too incomplete to have been made up as parables are), they also set me free from believing in the idea that Jesus had to die as a payment to God for my sins, because it too was something that I never understood. Why would God want His Son's blood as restitution for my sins? I know I'm a sinner and deserve punishment, but blood payment just makes God sound barbaric.

Borg and Crossan laid out the historical reality: just over a millennium ago, in 1097, St. Anselm of Canterbury wrote a book, Cur Deus Homo (translated, "When God Became Flesh") in which he applies the feudal relationship of peasant to lord to our relationship with God: "God must require a punishment, the payment of a price, before God can forgive our sins or crimes. Jesus is the price. The payment has been made, the debt has been satisfied."

This is called penal substitutionary atonement, and it basically says, "Jesus died in my place."

Except I couldn't understand that at all. The Romans and their Jewish collaborators didn't have any beef with me, so why are they executing this Christ because of me?

Because it is human inevitability to sin in this way.

That is why Jesus had to die, Borg and Crossan write. Our sinfulness means we will inevitably throw stones, make crowns of thorns, and ultimately crucify one another. God may well not have wanted Jesus to die, but He knew that it was the only way it could happen because of the way we are.

And yet, Christ's death still affects us. Rather than being a payment for our sins, it is, Mark writes in the Greek, a lutron, a ransom for our sins. A lutron isn't restitution, it's ransom. It is what you pay to liberate a slave from bondage, not to make up for breaking your neighbor's window with a baseball.

In other words, Mark is saying that Jesus died to liberate us from sin. And, as it turns out, that is what the church taught for the 1,067 years between the Crucifixion and St. Anselm: it is called the Christus Victor (Victorious Christ) atonement, and it essentially says that the work of Christ on the cross was to liberate us, for just as Paul says we are slaves to sin (Romans 6:20), Jesus liberates us from our slavery. Just as Moses liberated the Israelites from slavery in Egypt, so does Jesus liberate us all from slavery in the world entire.

We are free again through the cross. And for me, the light bulb finally went on. I could finally understand this terrible thing in a way that made sense.

That is the gift that Marcus Borg gave me. He enabled me to understand the death of my Lord and Savior. He enabled me to transform into a Christian whose faith wasn't threatened by the cross, but strengthened by it.

And what a precious gift that is. And how I shall miss the giver of that gift.

It is appropriate, then, that I end with this, a short excerpt from The Last Week on the relationship between death and resurrection:

Good Friday and Easter, death and resurrection together, are a central image in the New Testament for the path to a transformed self. The path involves dying to an old way of being and being reborn into a new way of being. Good Friday and Easter are about this path, the path of dying and rising, (and) of being born again.

May God welcome Marcus Borg, and one day all of us who believe, as reborn souls, if it is right that God should do so.

Yours in Christ,

Eric

When I first heard the news, I posted this to my Facebook page:

I just read about Bible scholar Marcus Borg passing away yesterday. I didn't agree with everything he said, especially about Easter and the nature of the Resurrection, but his book "The Last Week" that he co-wrote with John Dominic Crossan was (is) one of those "it changed my life" books, and months before he died, I had already planned to use that book as the template for my Lenten sermon series this year, to begin on Sunday, February 22. That sermon series takes on an added dimension for me with his, as he himself put it, "dying into God."

Go with God, Dr. Borg. Thanks for everything.

In The Last Week, Borg and Crossan, even though they argue for setting the factual nature of the Resurrection aside in order to approach it as a parable (something I never understood, because they are writing primarily about Mark's Gospel, and Mark's account of the Resurrection is too incomplete to have been made up as parables are), they also set me free from believing in the idea that Jesus had to die as a payment to God for my sins, because it too was something that I never understood. Why would God want His Son's blood as restitution for my sins? I know I'm a sinner and deserve punishment, but blood payment just makes God sound barbaric.

Borg and Crossan laid out the historical reality: just over a millennium ago, in 1097, St. Anselm of Canterbury wrote a book, Cur Deus Homo (translated, "When God Became Flesh") in which he applies the feudal relationship of peasant to lord to our relationship with God: "God must require a punishment, the payment of a price, before God can forgive our sins or crimes. Jesus is the price. The payment has been made, the debt has been satisfied."

This is called penal substitutionary atonement, and it basically says, "Jesus died in my place."

Except I couldn't understand that at all. The Romans and their Jewish collaborators didn't have any beef with me, so why are they executing this Christ because of me?

Because it is human inevitability to sin in this way.

That is why Jesus had to die, Borg and Crossan write. Our sinfulness means we will inevitably throw stones, make crowns of thorns, and ultimately crucify one another. God may well not have wanted Jesus to die, but He knew that it was the only way it could happen because of the way we are.

And yet, Christ's death still affects us. Rather than being a payment for our sins, it is, Mark writes in the Greek, a lutron, a ransom for our sins. A lutron isn't restitution, it's ransom. It is what you pay to liberate a slave from bondage, not to make up for breaking your neighbor's window with a baseball.

In other words, Mark is saying that Jesus died to liberate us from sin. And, as it turns out, that is what the church taught for the 1,067 years between the Crucifixion and St. Anselm: it is called the Christus Victor (Victorious Christ) atonement, and it essentially says that the work of Christ on the cross was to liberate us, for just as Paul says we are slaves to sin (Romans 6:20), Jesus liberates us from our slavery. Just as Moses liberated the Israelites from slavery in Egypt, so does Jesus liberate us all from slavery in the world entire.

We are free again through the cross. And for me, the light bulb finally went on. I could finally understand this terrible thing in a way that made sense.

That is the gift that Marcus Borg gave me. He enabled me to understand the death of my Lord and Savior. He enabled me to transform into a Christian whose faith wasn't threatened by the cross, but strengthened by it.

And what a precious gift that is. And how I shall miss the giver of that gift.

It is appropriate, then, that I end with this, a short excerpt from The Last Week on the relationship between death and resurrection:

Good Friday and Easter, death and resurrection together, are a central image in the New Testament for the path to a transformed self. The path involves dying to an old way of being and being reborn into a new way of being. Good Friday and Easter are about this path, the path of dying and rising, (and) of being born again.

May God welcome Marcus Borg, and one day all of us who believe, as reborn souls, if it is right that God should do so.

Yours in Christ,

Eric

Sunday, January 18, 2015

This Week's Sermon: "South Africa Rising"

Jesus went to Nazareth, where he had been raised. On the Sabbath he went to the synagogue as he normally did and stood up to read. 17 The synagogue assistant gave him the scroll from the prophet Isaiah. He unrolled the scroll and found the place where it was written:

18 The Spirit of the Lord is upon me, because the Lord has anointed me. He has sent me to preach good news to the poor, to proclaim release to the prisoners and recovery of sight to the blind, to liberate the oppressed, 19 and to proclaim the year of the Lord’s favor.

20 He rolled up the scroll, gave it back to the synagogue assistant, and sat down. Every eye in the synagogue was fixed on him. 21 He began to explain to them, “Today, this scripture has been fulfilled just as you heard it.” (Common English Bible)

“As One

Having Authority: Sermons that Changed the World,” Week One

“South

Africa Rising,” Luke 4:16-21

When I was in South Africa in the summer of 2006

on a mission trip sponsored by the Disciples’ overseas missions arm, Global

Ministries, my fellow missionaries and I stopped at the Hector Pieterson

memorial in Soweto, one of the impoverished suburbs of the big city of

Johannesburg. Upon the site where black

South African students rioted against apartheid in 1976 now stands a beautiful

engraved memorial to a young boy who was killed in those riots—and whose image

is now as indelibly carved into the collective memories of a great many people

as, say, the image of Martin Luther King, Jr. preaching in the capital, or the

image a young black man and a white police sergeant tearfully embracing one

another at the protests after the homicides of Michael Brown and Eric Garner.

This lasting image in South Africa is of this

young boy, Hector Pieterson, his body carried by Mbuyisa Makhubo as Hector’s

sister, Antoinette Sithole, rushes alongside them. In the land of another country that has known

so much grief as a result of a singular systematic injustice, the Hector

Pieterson memorial, with the enduring image of Hector himself, acts a burning

bush of sorts, akin to the burning bush that called out for Moses’s attention

in Exodus. And here, the memorial stands

as another burning bush calling out to be heard by all those who come across it

within the urban wilderness of a city.

And in this way, the dead do speak to us. They speak and they shout, they sing and

whisper and exhort, and they call out to us to this day. It is why we read their words and hear their

stories. And it is why I have chosen

this new sermon series, on how those long dead in the Bible continue to speak

to us as ones having authority through their words and their sermons.

This is a new sermon series to go along with the

new year, and it will take us all the way up to Ash Wednesday, which marks the

beginning of the church season of Lent.

For a while now, I have wanted to talk to all of you about the meaning

and significance of preaching, and this series allows me to do exactly that. The title for this series comes from the

assembled crowd’s reaction to Jesus’s Sermon on the Mount, where Matthew says

that they were astounded that He taught them as “one having authority,” rather

than one of their temple authorities. So…how

do we teach one another as one having authority? That’s what we’ll be working on together, and

each week for the next five weeks, we will be talking about one of the many

significant sermons that are given in the New Testament: the Sermon on the

Mount, Peter’s Pentecost sermon, Stephen’s farewell speech before his

martyrdom, and Paul’s address to the Areopagus.

But we begin this series by looking at Jesus’s first sermon in His

ministry as documented by Luke in his Gospel, and it is appropriate that we do

so on the weekend of Martin Luther King, Jr. Day because this resounding call

for justice from Isaiah 61 that Jesus preaches on is King’s message through and

through, just as it is as well the message of equality movements everywhere,

from the civil rights movement here in America to the anti-apartheid movement

in South Africa.

What I think we sometimes sanitize from our

memories is that these larger-than-life figures who are now universally revered

like King and like Nelson Mandela is that they were at one point demonized as

well. And what happens next in this

passage from Luke 4 ought to tell us a great deal about how divisive Jesus

likewise was too.

They tried to run him out of town and push him

off of a cliff to His death.

Meanwhile, we have tried to punish and discredit

religious teachers when they have gotten up on their pedestals and reminded us

of how woefully short we have fallen of God’s justice. King was, among other things, arrested,

imprisoned, and condemned as a communist, and Mandela was imprisoned for 27

years on Robben Island by the apartheid government of South Africa.

And we did those things. We were the synagogue crowd in Nazareth that

eventually tried to, literally, throw Jesus overboard. We may like to claim these civil rights

heroes as our own today, but they were not, and not, our own. They do not belong to us until we repent of

what we did to them.

Again, similarly, Jesus does not belong to us

until we repent of what we did to Him—of casting stones at Him, discrediting Him,

ultimately of crucifying Him, all because His message was so threatening to the

world we had built up that we could not tolerate His presence and His message

any longer. He had to go.

To be brutally honest, I don’t know if sometimes

we wouldn’t try to do the exact same thing today if Jesus came back in this

moment.

Luke 4—and by extension, Isaiah 61—is such a

difficult passage to preach on for that reason.

It reminds us that someone we desperately want to be universal—Jesus—was

not, is not, treated that way. It

reminds us that we are still sinners and hypocrites, ready to sit at His feet

and learn from Him one moment, and prepared to chuck Him down the canyon with Wile

E. Coyote the next, even though what Jesus is ultimately proclaiming—the year

of the Lord’s favor—is a reference to the Jubilee Year from the Torah, in which

all land is returned to its original owner, all slaves are freed, and all debts

forgiven, all things that Jesus’s original audience of impoverished working

people certainly needed, just like the racial and social justice King

proclaimed. Both were needed things, but

both were rejected initially, as were their messengers.

It is probably what we end up doing with all of

our heroes at some point. King was—and is—no

different. Almost universally revered

today, we still mostly sit at his feet and learn from him on this weekend when

we ponder him for a moment or three, and maybe for another day or two in

February as a part of Black History Month, but nevertheless, even the most

influential teachers tend not to always pop up in our heads when we need them

to the most. We tend to drown their

voices out in the moment of truth.

I think that’s why the synagogue crowd tried to

kill Jesus. Rather than listen to His

voice in this passage here today, they drowned out what He had to say—that the

promise of Isaiah 61 is fulfilled in Him, that in Him and through Him, there would

be good news for the poor, sight for the blind, freedom for the prisoners, and

liberty for the oppressed. It is a

promise for places like South Africa, like Jim Crow-era America, like Biblical

Israel where people still toiled along in the ranks of the hurt and the downtrodden

and the cast out.

Yet it is also a radical promise, a promise that

runs counter to every way in which the world works. So Jesus could not be tolerated, any more so

than King or Mandela in their days. He had to go, to be disposed of, as did

they.

That is why things like Martin Luther King Day

matter to us, and should matter to us, even if we think they don’t; because

each of us, in our own way, needs this promise that Jesus proclaims of freedom,

liberation, and wholeness, even if this world is not, or ever truly will be,

ready to hear it.

But Jesus is gone—He was crucified, resurrected,

and ascended into heaven, as has, in turn, King and Mandela. The dead may not speak as we speak, but that

does not mean that they do not speak at all.

It means that we are far too often deaf to their voices, voices which we

are not used to hearing, no matter how much practice we may have.

Yet transcend our deafness they sometimes still

do. Mandela did it as President of South

Africa, the first of a South Africa risen out of apartheid. King did it when he thundered on the steps of

the Lincoln Memorial in 1963 that he had a dream. And most important of all, Christ does it in

every word He speaks, every miracle He performs, every deed of power He puts

forth in the Gospels.

In this way, this Christ who begins His public

ministry in this story will change the world.

As must we all who dare to call ourselves

Christians, followers of this Christ.

May it be so.

Amen.

Rev. Eric Atcheson

Longview, Washington

January 18, 2015

(Original image via speakupmovement.org)

(Original image via speakupmovement.org)

Thursday, January 15, 2015

American Christians, We are NOT Persecuted Because of Our Faith

Earlier this week, Duke University (a United Methodist school) had announced plans to, beginning this Friday, allow its Muslim Students Association to use the chapel's tower to broadcast a weekly call to prayer on Fridays, the Muslim sabbath.

He thinks Vladimir Putin is a swell guy and protector of children for opposing marriage equality...even though a good rule for life is that if you and Vladimir Putin agree on something, you are most likely wrong.

Today, after a prejudiced son of a famous evangelist got his pantaloons all in a twist about it, Duke are showing true Christian cowardice by canceling the call to prayer.

What I find particularly rich is the quote from a Duke official in that second link saying, "It was clear that what was conceived as an effort to unify was not having the intended effect."

How either disingenuous or naive. Anyone familiar with Franklin Graham (son of Billy Graham) could tell you that he is not in the business of being unifying, he just plain doesn't give a shit about that. The guy throws verbal grenades for a living and claims he is doing it in the name of God:

He has called Islam a religion that "cannot be practiced in this country."

He has also called Islam a "religion of hatred."

He thinks Vladimir Putin is a swell guy and protector of children for opposing marriage equality...even though a good rule for life is that if you and Vladimir Putin agree on something, you are most likely wrong.

And the cherry on top of this total shit sundae is that his virulent Islamophobia didn't keep him from defending in print the genocidal military dictator of Sudan, Omar al-Bashir (whose ethnic cleansing was of mostly Christian populations).

To wit, Franklin Graham is a bigoted jerk. I don't throw that term "bigot" around lightly, but I mean it in every sense. There are people I disagree with profoundly on a variety of things who I'd still like to have coffee or a beer with. Franklin Graham is not one of them. He is nothing more than a bullying blowhard with a famous last name that he did not earn.

But he is also a symbol of a far greater plague within our faith.

There is this massive persecution complex that blights Christianity--whether it is in reaction to gay and lesbian men and women demanding (and receiving) equal rights, or non-Judeo-Christian faiths demanding (and receiving) equal air time and attention, there is this notion that we Jesus freaks are somehow being persecuted as a result, as thought rights are zero-sum and we cannot let others have more, lest we have fewer.

But stories like Duke University stripping down to its underwear, bending over, and telling Franklin Graham "Thank you, sir, may I have another" utterly disprove this misguided and hasty race towards victimhood we seem to be locked in.

Remember when, last year, the Christian charity World Vision announced they would allow the hiring of employees in same-sex marriages?

And remember how, two days later, they did a complete 180-degree reversal of that policy as the direct result of protests from Christians threatening to withdraw their sponsorships of impoverished children over this new policy?

That's not being persecuted, that's being privileged, privileged enough to have weight to throw around at a charity that was just trying to do right by its workers.

Remember when Obamacare's contraception mandate meant that Hobby Lobby had to provide contraception it objected to on religious grounds (to the extent that a corporation can believe in a religion) to its employees?

And remember how the United States Supreme Court agreed with them?

That's not being persecuted, that's being privileged, privileged enough to have your case be one of a bare handful heard before the highest court in the land.

So let's quit it with thinking that trying to elevate others to the same pedestal we have enjoyed in this country since 1776 really is about us being persecuted. We are exceedingly fortunate to be able to be Christians in the United States as opposed to being Christians in, say, North Korea (or Sudan, for that matter, ahem, Franklin).

Today, evidence of that reality was on full display. A major Christian university reversed course on a three-minute, once-a-week prayer for a non-Christian faith because Christians used their freedom of expression to protest it without any risk of recrimination.

That's not being persecuted, that's being privileged enough to persecute others and not have the cojones to call what you are doing for what it is--persecution.

It's being privileged enough to be openly hypocritical, as hypocritical as the scribes and Pharisees whom Jesus denounces at great length in the Gospels. And those chaps were nothing if not privileged in the fiercely hierarchical world of first-century Israel.

So be grateful, Christians, that you continue to occupy a place in American society where you can bully Muslims out of openly broadcasting their prayers. Personally, I'm more ashamed than grateful, but hey, they say gratitude is an attitude, so I'll get to work on fixing that straight away.

And while I'm busy doing that, Franklin Graham can go hit himself over the head with a hardcover Bible until it knocks him out, if only to prevent himself from hitting others over the head with it.

Yours in Christ,

Eric

Wednesday, January 14, 2015

Being Closeted in Death as well as in Life

One of my least favorite--but most important--parts of my job is performing funerals. I don't much care for it because as a pastor, it plays tricks with your head and your heart--you're working, but you're also often emotional and grieving as well--it is the blessing of the small church pastor that we get to know our congregants so well, and it is our curse that we miss them so deeply when they go to be with God.

And that chaos between having to do a job and needing to mourn can wrench you emotionally if you're not ready for it. It can lay you out but good. So burying the dead is a very tough part of the job for me, but because of its significance, I still strive to treat it with the utmost care. I don't always succeed--I remember one graveside service very vividly where I failed to list out the surviving family as had been requested, and another family member got up and did it for me while I stood there--but I try to.

That effort is why it wrenches me inside to read a story like this one, wherein Vanessa Collier, a 33-year-old deceased wife and mother of two daughter had her funeral canceled right when it was supposed to be taking place at 10:00 am last Saturday, January 10th.

Why? Because Vanessa is the wife of a woman, Christina Higley. She was a lesbian who had two daughters with her wife of three years, and the video montage that was to be shown at her funeral included an image of her and her wife kissing. The church wanted the image removed. Vanessa's family said no, and instead held the service at a nearby funeral home.

And I completely understand the family's refusal.

Now, as a pastor, I get wanting final say over what is displayed in your church's sanctuary--there are things I wouldn't allow if asked to for someone's wedding or funeral because it wouldn't do honor to God or the church.

But the deceased's family isn't something I get to edit out of their funeral. They aren't something (or somebodies) who the pastor gets to pretend doesn't exist, because they're going to be right there, front row center, to honor their loved one before God.

And I don't get to edit out who God made this deceased person to be--gay, straight, bisexual, transgendered, queer, any of it. I am emphatically not allowed to play God like that.

When you try to edit out something that big of someone's life--someone you are attempting, in every other sense, to honor in their death as you commit their soul to heaven--you're not honoring them, you're honoring a fake version of them. A version of them that you want them to be as opposed to who they actually were. You are not committing to God's care the person, you are committing the idea of a person who never really was.

Which is not what the church is about. It is not what the church has ever been about, or ever should be about, although I fear that is what we are about, because it is what we have done to so many living gay and lesbian people: forced them to remain closeted for far too long. And, as it turns out, we are trying to closet them in death as well as in life. The same destructive things that we claim to be moving away from in reaching out to our living gay and lesbian brothers and sisters are still very much present in our treatment of them once they have passed from this kingdom into God's kingdom.

But I also have friends...seminary classmates...ministry colleagues, who are gay. I have met their spouses, broken bread with them, shared laughter and joy and sorrow alike with them. I could not imagine honoring one and pretending the relationship with the other did not exist. I couldn't fathom it. It would be a lie. And the Bible does indeed have some pretty strong things to say about bearing false witness.

So let me say this, openly and plainly: I do not, and will not, ever put as a condition of performing a funeral service that the person's sexual orientation be hidden. Rather, with God and family willing, I would want to see sexual identity celebrated as a part of a person's divinely-given identity. If you are in the Longview/Vancouver/Portland corridor and have been turned away from a church for wanting to have a gay or lesbian loved one's funeral there, message me. I would be happy and humbled to officiate their funeral, despite funerals being difficult for me to do. I cannot promise I'll be the same as the pastor or church you first asked, but I can promise that I will strive to do justice and honor to your loved one and to their innate connection to God.

Because a church that does not honor God's children is, in the end, not a church that honors God.

If this is somehow not right of me to do, may God have mercy on me.

Yours in Christ,

Eric

And that chaos between having to do a job and needing to mourn can wrench you emotionally if you're not ready for it. It can lay you out but good. So burying the dead is a very tough part of the job for me, but because of its significance, I still strive to treat it with the utmost care. I don't always succeed--I remember one graveside service very vividly where I failed to list out the surviving family as had been requested, and another family member got up and did it for me while I stood there--but I try to.

That effort is why it wrenches me inside to read a story like this one, wherein Vanessa Collier, a 33-year-old deceased wife and mother of two daughter had her funeral canceled right when it was supposed to be taking place at 10:00 am last Saturday, January 10th.

Why? Because Vanessa is the wife of a woman, Christina Higley. She was a lesbian who had two daughters with her wife of three years, and the video montage that was to be shown at her funeral included an image of her and her wife kissing. The church wanted the image removed. Vanessa's family said no, and instead held the service at a nearby funeral home.

And I completely understand the family's refusal.

Now, as a pastor, I get wanting final say over what is displayed in your church's sanctuary--there are things I wouldn't allow if asked to for someone's wedding or funeral because it wouldn't do honor to God or the church.

But the deceased's family isn't something I get to edit out of their funeral. They aren't something (or somebodies) who the pastor gets to pretend doesn't exist, because they're going to be right there, front row center, to honor their loved one before God.

And I don't get to edit out who God made this deceased person to be--gay, straight, bisexual, transgendered, queer, any of it. I am emphatically not allowed to play God like that.

When you try to edit out something that big of someone's life--someone you are attempting, in every other sense, to honor in their death as you commit their soul to heaven--you're not honoring them, you're honoring a fake version of them. A version of them that you want them to be as opposed to who they actually were. You are not committing to God's care the person, you are committing the idea of a person who never really was.

Which is not what the church is about. It is not what the church has ever been about, or ever should be about, although I fear that is what we are about, because it is what we have done to so many living gay and lesbian people: forced them to remain closeted for far too long. And, as it turns out, we are trying to closet them in death as well as in life. The same destructive things that we claim to be moving away from in reaching out to our living gay and lesbian brothers and sisters are still very much present in our treatment of them once they have passed from this kingdom into God's kingdom.

But I also have friends...seminary classmates...ministry colleagues, who are gay. I have met their spouses, broken bread with them, shared laughter and joy and sorrow alike with them. I could not imagine honoring one and pretending the relationship with the other did not exist. I couldn't fathom it. It would be a lie. And the Bible does indeed have some pretty strong things to say about bearing false witness.

So let me say this, openly and plainly: I do not, and will not, ever put as a condition of performing a funeral service that the person's sexual orientation be hidden. Rather, with God and family willing, I would want to see sexual identity celebrated as a part of a person's divinely-given identity. If you are in the Longview/Vancouver/Portland corridor and have been turned away from a church for wanting to have a gay or lesbian loved one's funeral there, message me. I would be happy and humbled to officiate their funeral, despite funerals being difficult for me to do. I cannot promise I'll be the same as the pastor or church you first asked, but I can promise that I will strive to do justice and honor to your loved one and to their innate connection to God.

Because a church that does not honor God's children is, in the end, not a church that honors God.

If this is somehow not right of me to do, may God have mercy on me.

Yours in Christ,

Eric

Sunday, January 11, 2015

This Week's Sermon: "Out of Bethlehem"

Matthew 2:1-12

After Jesus was born in Bethlehem in the territory of Judea during the rule of King Herod, magi came from the east to Jerusalem. 2 They asked, “Where is the newborn king of the Jews? We’ve seen his star in the east, and we’ve come to honor him.” 3 When King Herod heard this, he was troubled, and everyone in Jerusalem was troubled with him. 4 He gathered all the chief priests and the legal experts and asked them where the Christ was to be born. 5 They said, “In Bethlehem of Judea, for this is what the prophet wrote:

6 You, Bethlehem, land of Judah, by no means are you least among the rulers of Judah, because from you will come one who governs, who will shepherd my people Israel.”

7 Then Herod secretly called for the magi and found out from them the time when the star had first appeared. 8 He sent them to Bethlehem, saying, “Go and search carefully for the child. When you’ve found him, report to me so that I too may go and honor him.” 9 When they heard the king, they went; and look, the star they had seen in the east went ahead of them until it stood over the place where the child was. 10 When they saw the star, they were filled with joy. 11 They entered the house and saw the child with Mary his mother. Falling to their knees, they honored him. Then they opened their treasure chests and presented him with gifts of gold, frankincense, and myrrh. 12 Because they were warned in a dream not to return to Herod, they went back to their own country by another route. (Common English Bible)

After Jesus was born in Bethlehem in the territory of Judea during the rule of King Herod, magi came from the east to Jerusalem. 2 They asked, “Where is the newborn king of the Jews? We’ve seen his star in the east, and we’ve come to honor him.” 3 When King Herod heard this, he was troubled, and everyone in Jerusalem was troubled with him. 4 He gathered all the chief priests and the legal experts and asked them where the Christ was to be born. 5 They said, “In Bethlehem of Judea, for this is what the prophet wrote:

6 You, Bethlehem, land of Judah, by no means are you least among the rulers of Judah, because from you will come one who governs, who will shepherd my people Israel.”

7 Then Herod secretly called for the magi and found out from them the time when the star had first appeared. 8 He sent them to Bethlehem, saying, “Go and search carefully for the child. When you’ve found him, report to me so that I too may go and honor him.” 9 When they heard the king, they went; and look, the star they had seen in the east went ahead of them until it stood over the place where the child was. 10 When they saw the star, they were filled with joy. 11 They entered the house and saw the child with Mary his mother. Falling to their knees, they honored him. Then they opened their treasure chests and presented him with gifts of gold, frankincense, and myrrh. 12 Because they were warned in a dream not to return to Herod, they went back to their own country by another route. (Common English Bible)

“Out of

Bethlehem,” Matthew 2:1-12

I have to be honest—I struggle so much sometimes

with the commandment against lying. Not

because I’m a habitual or compulsive liar, mind you—I’m not. Nor do I think for a second that lying doesn’t

usually do damage in the end. But

sometimes…oftentimes, in the midst of a massive, monumental crisis, it is by

far the lesser of two evils.

In the defining crisis of our era—September 11,

2001—I came across this story about the heroic efforts of the search and rescue

dogs, hundreds of them, that were deployed to find any survivors…which, of

course, on that day, were few and far between to be found. And that grim reality ate at these canine

rescuers in ways I honestly did not realize, as Petcentric emphasizes:

(9/11)

created a remarkable elevation of the human-canine bond, where dogs and people

worked together, understood each other’s needs, and helped each other on

physical, emotional, and even spiritual levels, to get through a crisis neither

species understood…

As the dogs

worked with their handlers up to 16 grueling hours a day, it soon became

apparent that the dogs were nearly as distraught as the human rescuers when

there were so few survivors to be found.

For the human rescue workers, the lack of survivors made the attacks

feel ever more horrific and tragic. For

the dogs trained to find survivors, thought, it felt like a personal failure.

From a SAR

(search and rescue) dog’s perspective, being a good dog means you do your job

and find the people you’re supposed to find.

The long days of climbing through rubble, squeezing through tight

spaces, sniffing every nook and cranny and finding no living people caused the

dogs great stress, and they seemed to think this failure was their fault. Handlers and other rescue workers had to

regularly hide in the rubble in order to give the dogs a successful find to

keep their spirits up. (emphasis mine)

I mean…if its deception, it is the most

kind-hearted and generous sort of deception I can possibly think of, especially

considering just how demoralized the human handlers themselves had to have

been. But that has always been the way

of things—or should be the way of things, I should say—in times of great

crisis: you take great care to look out for one another, even at and especially

at the risk of putting your own needs and your own wants on the back

burner. And that’s what the magi do.

On the surface, I think this story about the magi

(or wise men, or astrologers, or rocket scientists, or what have you…) tends to

get swept up in the rest of the sweetness in the Christmas story, and I imagine there are a lot of massages taking place today about the generosity of the gifts and the reverence of the worship and that sort of thing, and that is all well and good, but it is also incomplete. If that is all the story were about, Matthew could have and would have dispensed with it in just a few sentences, not twelve verses.

In all

actuality, this story is in fact an incredibly harrowing tale of palace intrigue and,

ultimately, of betrayal of a king—King Herod, who summons the magi for a

specific reason: to ascertain a threat to him.

Jesus.

Herod is asking the wise men to do this in secret—as

Matthew writes in verse 7, “Herod secretly called for the wise men…then he sent

them to Bethlehem.” What we remember

today as an act of devout worship of the Christ child by complete strangers in

fact began as a cloak-and-dagger spy mission of sorts—Herod is basically

charging the magi to go and see what this new king is really like and report

back on whether or not he is a real threat or not.

Of course, Jesus is a true threat to Herod, but

not this particular Herod—this Herod kicks the bucket not long after this whole

escapade, and it is his son, Herod Antipas, who ends up having to deal with the

adult Jesus, as Luke’s Gospel tells us that Herod Antipas interrogated Jesus at

Pilate’s behest during the Passion, all to no avail.

And here, 30 years earlier, Antipas’s father,

Herod the Great, likewise goes to great lengths in his efforts against this

Jesus of Nazareth, and likewise it is ultimately all to no avail. Herod the Great, though, is far more barbaric

than his son, and when the magi do not return to Herod, he orders the murder of

every boy in Bethlehem under the age of two in the hopes of exterminating said

threat to his kingship, but by that time, Joseph, Mary, and Jesus are in the

wind and on their way into Egypt.

They are out of Bethlehem. They are out of the dragon’s nest. They are out of the place that should have

been one of great joy for them—after all, their son was born there, and Joseph’s

family is originally from there (because he is of the line of King David, who

was from Bethlehem), and instead what Bethlehem becomes is the site of yet

another slaughter at the behest of a strongman who couldn’t bear to countenance

the thought that his precious hold on power might one day end.

And so the magi end up lying to protect the baby

Jesus. They deceive Herod utterly, and

leave him in the lurch by returning to their homeland rather than to Jerusalem

to report back as presumably had been previously agreed upon. They repay Herod’s own secrecy with still

more secrecy, but every indication is that the world, and humanity itself, is

far better off for them having done so.

This level of duplicity and deception is actually

a tradition the church can be proud of: from hiding European Jews from Nazi

soldiers during the Second World War to smuggling persecuted Christians out of danger

in Central American countries run by Cold War dictators throughout the 20th

century, there is in fact a long and great history of the church helping its

brothers and sisters in Christ do what Jesus, Mary, and Joseph did once the

magi had departed: get out of Bethlehem.

Realistically, we do not have anything as

dramatic as an imminent massacre of our newborns to escape from, but each of us

does, I think, have things that we can, we should, we need to escape from:

whether it is addiction, or our treatment of people we think of as different or

less than us, or the exploitation of child labor in our shopping habits, there

are any number of horrific sins we uphold in our daily lives, maybe without

even thinking about it. We may seek the

Bethlehem of Jesus’s birth, but what we are prone to creating is the Bethlehem

of Herod the Great’s slaughter.

In this way, sadly, while we are clearly meant to

take after the wise men in their loyalty to, and reverence of, Jesus, we really

ought to remind ourselves more of Herod…if we are to be truly honest with ourselves. But if we are able to engage in such naked

honesty, we are also capable of realizing that we truly need not be that

monster. We are better than that. We are better than Herod.

That is why we are capable of creating the lies

that build up, say, search-and-rescue dogs whose work, even when ultimately

fruitless like it was on September 11th, is still of such great

importance. It is why we are capable of

creating the lies that protect the newborn Savior of humanity. And it is why we can still lift each other

out of the destructive Bethlehem of Herod and back into the peaceful Bethlehem

of David and of Jesus.

May that be our goal this year, and the year

after, and after that, as we strive to remain true to the devotedness of a

small band of believers who came to worship Christ at great risk to themselves.

Rev. Eric Atcheson

Longview, Washington

January 11, 2015

Wednesday, January 7, 2015

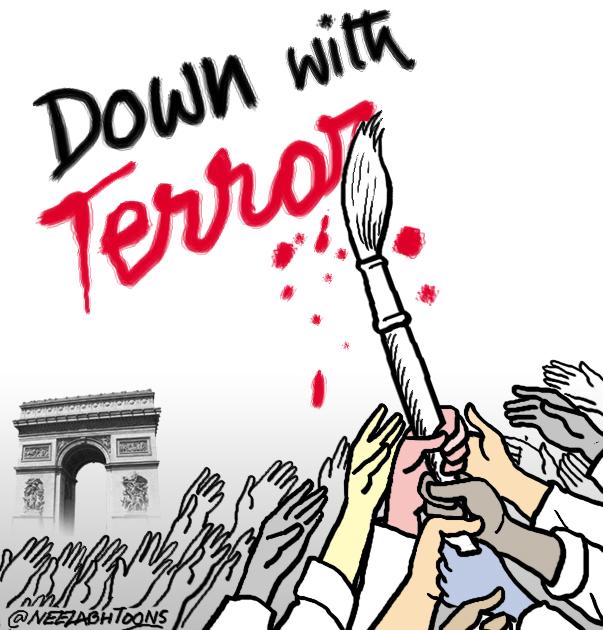

Some Strongly Worded Thoughts on the Sinfulness of Religious Violence

Overnight in the States, a terrorist attack struck in the heart of Paris, as hooded gunmen wielding Kalishnikov submachine guns entered the offices of the Charlie Hebdo satire magazine and proceeded to open fire, killing four cartoonists and eight staffers. Part of the reason this is such horrifying news is that while mass shootings are now sadly a fact of life here in the US, they are not so in Europe. And for this, my heart goes out to France. Because I, and just about every other American, have been there.

But another part of the reason this story so horrifying is that the gunmen were also filmed shouting the words, "God is great," and "We have avenged the Prophet."

Both of these phrases are references to Islam. "God is great," translated into Arabic, is "Allahu ackbar," and it is known as the Takbir. The "Prophet" is a reference to the last prophet in Islamic tradition, and the founder of Islam itself, Muhammad. The Charlie Hebdo cartoonists had a history of both satirizing religion (including both Christianity and Islam) and of depicting Muhammad in image form, something that is prohibited in Islam.

The shooting was an act of religious violence.

And yet, here is where religion is supposed to step in--to prevent us from acting on our basest desires for violence and revenge when we feel wronged. It isn't supposed to give us a pretext for doing so.

"Turn the other cheek?" That's not just a saying in Christian tradition--because Jesus is also considered a prophet in Islamic tradition, it is a teaching that is a part of their history as well as ours.

Somebody offends you? You turn the other cheek. You take the insult with grace and you respond with words, not weapons. You respond constructively, not destructively.

Personally, as a devoutly religious person, I still find some religious satire useful because it forces me to examine myself. For all the valid critiques of a show like, say, South Park, over its tastelessness and gratuitous offensiveness, I maintain this: every time it has stepped forward to skewer religion, it has hit the nail right on the head, whether it has been about contemporary Christian music, Mormonism, or Mel Gibson's The Passion of the Christ, and so on.

Now, that doesn't mean I necessarily agree with what Charlie Hebdo has said about religion, but that shouldn't matter. As the patron saint of religious criticism Voltaire famously said, "I may disagree with what you say, but I will defend to the death your right to say it." (Voltaire actually was also virulently Islamophobic, making his comments about tolerance of religion and expression particularly ironic, but the sentiment of respecting freedom of expression has rightfully endured.)

The Charlie Hebdo journalists had a right to publish their expressions, no matter how tasteless I or anyone else might find them. It has to be that way for freedom to work--not just freedom of the press, but also, it must be noted, freedom of religion.

The only way I know that I can teach whatever I feel led to teach is if the other pastor, or the other church, or the other religious community down the road from me can teach whatever they are teaching.