September 2016: "When There's a Will"

Dear Church,

When my first childhood pet, a little danio fish named Junior, died, I wrote a will for him, entitling me to some obscenely large amount of money (I think I just wrote a one and a bunch of zeros after it...I was just a kid!), and presented the will to my parents, expecting to get paid off.

My parents, as many of you know, are attorneys by trade. They were touched, but knew much more than I did about how wills worked. I got a hug, but no cash.

And I know now that the hug was far more important in the end.

Because I must confess to you--this has been a tough year for me, emotionally and spiritually, as your pastor. Having Agnes Staggs and Doc Davenport pass away on the same week earlier this year, followed by Rosier Keller over the summer, has left me at times in an ongoing process of grieving for whom we as a church community have lost, and whom I personally have lost in the people whom I counted as friends and congregants.

This is on top of the other people whom we have lost over my five years here as your pastor--I have mourned each and every one of them, as I know you have as well. We have lost some truly kindred souls, and while we take reassurance in the knowledge that they are all now with the Lord, it still falls to us to remember them with great fondness and affection here in their stead.

Many of them in fact took it upon themselves to make sure that their memory and legacy would speak volumes as to their priorities and values as Christians by crafting a last will and testament to ensure that the people and organizations that they valued most would continue to be valued by them even after they were gone. Several who chose to do so in this way elected to specifically remember First Christian Church in their wills, and the gifts that they left to our faith family have gone so very far indeed in helping to sustain the important, life-giving presence that we provide to one another and, even more importantly, to the wider community in the form of our mission work with organizations like Kessler Elementary School and the Emergency Support Shelter.

There is a way for you too to remember First Christian Church--and/or our denomination, the Christian Church (Disciples of Christ)--in your own will. If you do not have a will, you can speak to a legal expert (not me--the laws I interpret only come from the Bible!) about crafting one. If you already have a will, you can speak to a lawyer about adding a codicil to your existing will in order to remember either FCC or the CC (DOC), in addition to any other number of charities or organizations you wish to make an estate gift to!

Our denomination is able to help as well--the Christian Church Foundation, which for many years very ably oversaw our church's humble investment fund, has experts on staff who can point you in the right direction to make sure your estate gift is properly documented and executed. You can call them toll-free at 1-800-668-8016, or you can find them online at christianchurchfoundation.org.

Estate planning is something that is prudent to do in general in order to ensure that any provisions for your children and/or family are protected, but it can also be something to reflect your values and priorities even after you are gone. I would humbly ask you to consider it as a means for ensuring that your voice continues to express your esteem, whether it is for FCC, or the Disciples of Christ denomination, or the Emergency Support Shelter, or anyone and anything else that is near and dear to your heart.

I have been in a position now for several years to see just how big a difference such gifts can make. And that difference can truly be life-changing.

Yours in Christ,

Pastor Eric

Wow, it's almost autumn already! After a full summer of going verse-by-verse through the life and reign of King Solomon in 1 Kings, we'll be returning to some more thematic preaching in the fall with two sermon series, the first of which is centered around famous verses from Scripture that we have a tendency to take out of context--verses like John 3:16 ("For God so loved the world...") or Philippians 4:13 ("I can do all things..."). We'll begin that sermon series with one passage from the Hebrew Bible--Jeremiah 29 specifically--before moving into several weeks of New Testament lessons and Scriptures. If ever you wondered how it has gotten to be so tempted to taking Bible verses out of context, or how you can try to break yourself of that habit (or to prevent yourself from picking up that habit!), this is a sermon series you won't want to miss! Once I'm back in the saddle though, I'll be running into this new sermon series full-speed, and I hope you'll share in my enthusiasm for unpacking these Scriptures together!

New sermon series: “Contextual Chaos: How to Stop Taking the Bible Out of Context”

September 11: “Zone Rouge,” Jeremiah 29:4-15

September 18: “Three Hundred Denarii,” John 12:1-11

September 25: “The Immovable Ladder,” 1 Thessalonians 4:13-18

October 2: “The Croix de Guerre,” Philippians 4:10-20

October 9: “Earthly and Heavenly Things,” John 3:10-21

"I too decided to write an orderly account for you, dear Theophilus, so that you may know the truth..." -Luke 1:3-4. A collection of sermons, columns, and other semi-orderly thoughts on life, faith, and the mission of God's church from a millennial pastor.

Friday, August 26, 2016

Thursday, August 25, 2016

My Dogs Write Again

Dear Apelike Manservant Who Lives to Spoil Us,

It's us again. Even though we lack the opposable thumbs with which to actually, you know, write, we have things on our minds that we want to say, and you humans have a saying about when there's a will, there's a way.

We have some questions for you.

Why do you insist on feeding us this gruel you put in our bowls when we *know* you feast on morsels of delicious goodness everyday at a table that for some inexplicable reason we are not allowed on?

Why do you keep trying to get us to "share" bones and toys with each other? This is clearly not an optimal system, and we each demand to have all the bones. Make of that ultimatum what you will.

And why do you humans so extensively justify every single thing that you do? Like, we don't need more than one reason: our ears are itchy, so we scratch them. Some other dog's butt smells enticing, so we sniff it. That's it. That's all the justification we need.

Why do you lot turn somersaults over trying to justify how mean and cruel you are to your fellow servants-who-should-live-to-spoil-us? Why do you keep telling yourselves "Well, all they'll learn is dependency?" Hello...y'all came into this world the same way we perpetually exist in it: needing attention, food, and potty breaks pretty much around the clock.

Dependence--at least some of it--is in your blood. Just like it's in ours. But we're okay being dependent on you and Carrie, because you're nice to us and let us sunbathe on the couch.

Is it really so hard that everyone be as nice to each other as they are to their own pets? I know we're terrible to each other--hold on, one of us has to lick the other's eyeball in order to steal a bone--but you're supposed to be smarter at living us. That's why we wear the leashes instead of you.

You use those smarts, though, to not always make peoples' lives better, or more loving, but to justify *you* making *your* life better at the expense of someone else.

What, you're asking if *we* do that? Of course we do. But we're dogs. We don't know any better.

You do. You all do.

So why not, you know, try doing better, and being better, to each other? Don't just turn the other way when you see suffering, don't just excuse your inaction away, but actually do something, even if it's just sitting up and barking at a fly?

Far be it for us to question you, our butlers. But this is our world, and you just live here (to serve us). So, we're laying down the law: embrace your dependence on each other. Stop acting like you're on a freaking island. And if you are on an island, take us with you. It's probably sunny there, and did we mention that we love the sun?

With love, face licks, and utterly noxious gas,

Dame Frida Koala and Sir Henry Wiggly

Dame Frida Koala (the fluffy white one) and Sir Henry Wiggly (the perked-up cinnamon-and-white one) are the bestest dogs in the whole wide world except for Rowlf from the Muppets. C and I love them very, very much.

Sunday, August 21, 2016

This Week's Sermon: "Jeroboam's Kingdom"

1 Kings 11:26-43

Now Nebat’s son Jeroboam was an Ephraimite from Zeredah. His mother’s name was Zeruah; she was a widow. Although he was one of Solomon’s own officials, Jeroboam fought against the king. 27 This is the story of why Jeroboam fought against the king: Solomon had built the stepped structure and repaired the broken wall in his father David’s City. 28 Now Jeroboam was a strong and honorable man. Solomon saw how well this youth did his work. So he appointed him over all the work gang of Joseph’s house.

29 At that time, when Jeroboam left Jerusalem, Ahijah the prophet of Shiloh met him along the way. Ahijah was wearing a new garment. The two of them were alone in the country. 30 Ahijah tore his new garment into twelve pieces. 31 He said to Jeroboam, “Take ten pieces, because Israel’s God, the Lord, has said, ‘Look, I am about to tear the kingdom from Solomon’s hand. I will give you ten tribes. 32 But I will leave him one tribe on account of my servant David and on account of Jerusalem, the city I have chosen from all the tribes of Israel. 33 I am doing this because they have abandoned me and worshipped the Sidonian goddess Astarte, the Moabite god Chemosh, and the Ammonite god Milcom. They haven’t walked in my ways by doing what is right in my eyes—keeping my laws and judgments—as Solomon’s father David did. 34 But I won’t take the whole kingdom from his hand. I will keep him as ruler throughout his lifetime on account of my servant David, who did keep my commands and my laws. 35 I will take the kingdom from the hand of Solomon’s son, and I will give you ten tribes. 36 I will give his son a single tribe so that my servant David will always have a lamp before me in Jerusalem, the city that I chose for myself to place my name. 37 But I will accept you, and you will rule over all that you could desire. You will be king of Israel. 38 If you listen to all that I command and walk in my ways, if you do what is right in my eyes, keeping my laws and my commands just as my servant David did, then I will be with you and I will build you a lasting dynasty just as I did for David. I will give you Israel. 39 I will humble David’s descendants by means of all this, though not forever.’” 40 Then Solomon tried to kill Jeroboam. But Jeroboam fled to Egypt and its king Shishak. Jeroboam remained in Egypt until Solomon died.

41 The rest of Solomon’s deeds, including all that he did and all his wisdom, aren’t they written in the official records of Solomon? 42 The amount of time Solomon ruled over all Israel in Jerusalem was forty years. 43 Then Solomon lay down with his ancestors. He was buried in his father David’s City, and Rehoboam his son succeeded him as king. (Common English Bible)

Now Nebat’s son Jeroboam was an Ephraimite from Zeredah. His mother’s name was Zeruah; she was a widow. Although he was one of Solomon’s own officials, Jeroboam fought against the king. 27 This is the story of why Jeroboam fought against the king: Solomon had built the stepped structure and repaired the broken wall in his father David’s City. 28 Now Jeroboam was a strong and honorable man. Solomon saw how well this youth did his work. So he appointed him over all the work gang of Joseph’s house.

29 At that time, when Jeroboam left Jerusalem, Ahijah the prophet of Shiloh met him along the way. Ahijah was wearing a new garment. The two of them were alone in the country. 30 Ahijah tore his new garment into twelve pieces. 31 He said to Jeroboam, “Take ten pieces, because Israel’s God, the Lord, has said, ‘Look, I am about to tear the kingdom from Solomon’s hand. I will give you ten tribes. 32 But I will leave him one tribe on account of my servant David and on account of Jerusalem, the city I have chosen from all the tribes of Israel. 33 I am doing this because they have abandoned me and worshipped the Sidonian goddess Astarte, the Moabite god Chemosh, and the Ammonite god Milcom. They haven’t walked in my ways by doing what is right in my eyes—keeping my laws and judgments—as Solomon’s father David did. 34 But I won’t take the whole kingdom from his hand. I will keep him as ruler throughout his lifetime on account of my servant David, who did keep my commands and my laws. 35 I will take the kingdom from the hand of Solomon’s son, and I will give you ten tribes. 36 I will give his son a single tribe so that my servant David will always have a lamp before me in Jerusalem, the city that I chose for myself to place my name. 37 But I will accept you, and you will rule over all that you could desire. You will be king of Israel. 38 If you listen to all that I command and walk in my ways, if you do what is right in my eyes, keeping my laws and my commands just as my servant David did, then I will be with you and I will build you a lasting dynasty just as I did for David. I will give you Israel. 39 I will humble David’s descendants by means of all this, though not forever.’” 40 Then Solomon tried to kill Jeroboam. But Jeroboam fled to Egypt and its king Shishak. Jeroboam remained in Egypt until Solomon died.

41 The rest of Solomon’s deeds, including all that he did and all his wisdom, aren’t they written in the official records of Solomon? 42 The amount of time Solomon ruled over all Israel in Jerusalem was forty years. 43 Then Solomon lay down with his ancestors. He was buried in his father David’s City, and Rehoboam his son succeeded him as king. (Common English Bible)

The Dreaming Architect:

Solomon, Son of David & Bathsheba, King of Israel,” Week Ten

It

is an image that for me may well go down in my mind as one of the iconic images

of my time on earth, the way that, say, the face of Omayra Sanchez Garzon was

in the 1980s, or the John Filo photograph of a dying Jeffrey Miller at the Kent

State University shooting in the 1970s was.

This

time, it is a young African-American woman, later discovered to be Ieshia

Evans, a nurse and mother from New York City, standing peacefully, serenely,

and utterly alone in a long, flowing dress as in front of her stands a long

line of police officers dressed to the nines in SWAT team gear. Two of those

officers rush forward to arrest her at a protest in Louisiana.

And

she stands there. Simply. Elegantly. Gracefully. Proudly.

It

is what she said afterwards, though, that must be shared and repeated today,

just four days after an African-American man was shot and killed by a Kelso

police officer after the man apparently physically attacked the officer with a

hefty walking stick. Evans said: “I just need you people to know, I appreciate

the well wishes and love, but this is the work of God. I am a vessel! Glory to

the most high! I’m glad I’m alive and safe and that there were no casualties

that I have witnessed firsthand.”

She

also went out of her way to publicly thank a kind officer at the county jail

where she was kept saw to it that all of the protesters were treated well.

And

that is what we can be capable of, when we want to be: a kindness and

fundamental compassion that sees the humanity in the other, even when we

protest, even when we rebel. Part of the reason why it was so heartbreaking

that the shooting of the five police officers took place in Dallas is because

the Dallas police department has become a truly excellent police force over the

past several years and had a strong working relationship, built on mutual

respect, with its protesters.

So

when our own sheriff, Mark Nelson, says at a press conference earlier this

week, “I think if people want to come and express their thoughts and their

feelings about things that have gone on here, they can do that, I’m not really

worried about it,” I give thanks for that humanity in law enforcement officers

and protesters alike, because when we have faith in the good willing out, like

Sheriff Nelson has, like Ieshia Evans has, then maybe we can still reach for

faith, rather than for outrage like we are wont to do, and like Jeroboam is

wont to do here in the final part of 1 Kings 11.

This

is the final installment of a summer sermon series in the mold of one,

stylistically, just like it a couple of years ago in 2014, when, if you’ll

remember, we spent most of the summer reading verse-by-verse through the

beginning of Acts, we have once more taken on one big narrative in Scripture.

Only

this time, that narrative has been the life and reign of King Solomon, a

fascinating figure in Israelite history who has probably been somewhat

mythologized and made into a King Arthur-esque national legend over the years,

but who nonetheless represents an epoch centered around a singular truth that

was not achieved again for hundreds of years, and then again for thousands:

ruling over Israel as a unified and independent kingdom.

Believe

it or not, a unified and independent Israel is a rarity in history. After

Solomon, an independent and unified Israel would only really exist twice:

during the short reign of the Maccabees (of whom you have probably heard via

the Hanukkah story), and during present history since 1946.

So

Solomon’s reign—and his father David’s before him—is unique. How Solomon is

remembered matters because of it. And we’ve gotten a chance to read this

dreaming architect’s story from his building of the original temple in

Jerusalem after receiving divine wisdom from the Lord in the dream all the way

up to today’s story of the visit from the queen of Sheba, which represented in

many ways the absolute pinnacle for Solomon and his reign, to today’s story

just one chapter later, in which we continue to see how the seeds of Solomon’s

spiritual and political downfall were sown after the story two weeks ago of God

telling Solomon basically as such. Last week, we met two other agents of that

downfall—the external enemies to Solomon named Hadad and Rezon, and today, we

meet Jeroboam, the internal enemy of Solomon who rebels, first unsuccessfully,

but later, once Solomon has died, successfully against the new king, Rehoboam.

It

is easy at first glance to sympathize with Jeroboam—the text calls him a

“strong and honorable man,” and the prophet Ahijah charges Jeroboam with

reigning over ten of the twelve tribes of Israel because Solomon has, as we’ve

talked about over the past two weeks, drifted away from the Lord.

But

that is the exact route that Jeroboam will go down as well (spoiler alert). His

portion of the kingdom will not include Jerusalem and, by extension, Solomon’s

temple, meaning Jeroboam has to come up with a different way for his brand-new

constituents to worship God. So he crafts two golden calves for them (where

have we heard this story before?), tells the people “Here are your gods” (where

have we heard this before?) and another prophet of God appears and curses

Jeroboam, not blesses him.

And

the sad thing is, hindsight is 20/20 and all, but you really probably could

have seen this coming from another detail in this passage: Solomon put Jeroboam

in charge of the—what the texts says, but is really a euphemism—“work crews,”

basically, the kingdom’s slaves. Jeroboam’s job is to be the chief slave driver

for Solomon. So “strong and honorable” he likely, in all truth, was really not.

Which

is a tough thing to have to cope with, when your leaders or the people in your

everyday life are not always so strong and honorable. That, I don’t think, has

happened here this week, at least not by our leaders. Like I said, the Cowlitz

County Sheriff’s Office under Sheriff Nelson has done good work with the

unenviable job of reviewing the death of another person and managing potential

fallout. And the Vancouver chapter of Black Lives Matter has been similarly

very measured—like BLM as a whole, it encouraged engagement with law

enforcement and elected leaders this week, and has maintained BLM’s blanket

policy of rejecting all forms of violent protest.

No,

what needs to be discussed—and I hope you won’t immediately put your guard up

to me when I say this—is the immediate reaction to the news when it broke on

Wednesday morning. And that reaction on social media was, basically, “The Daily

News is being race-baiting and divisive by reporting the victim’s race.” (I’m

paraphrasing and removing significant amounts of vulgarity.)

Now,

let’s stop for a moment and consider: Cowlitz County is less than 1%

African-American, and nearly 89% white. If TDN hadn’t reported any information

on the person’s race at all, what race would we most likely assume he was? Probably

white. So by deliberately omitting a salient detail, TDN would be misleading

you, which is the exact opposite job of print media and its entire mission.

Nor

were many of the comments directed towards uplifting the officer, who was

beaten badly enough—and you can see part of it, the footage from CCTV has been

made available by the sheriff online—that he had to be taken to St. John

Hospital. But for all of the rhetoric of #BlueLivesMatter that is out there,

that was clearly not the foremost concern on display by the commenters in our

community—it was erasing this victim’s blackness.

And

that matters, because there is so little color and diversity that does exist

within our community. We can say that our leaders divide us by race, but we

have largely done that to ourselves over centuries and centuries of both legal

and de facto segregation. How many of us have a significant number of friends

of color in our community? I know I don’t—the vast majority of my friends of

other ethnic and racial backgrounds come from my time in the San Francisco Bay

Area or Seattle.

What

does any of this have to do with this week’s story of Jeroboam? Jeroboam, as

Ahijaah prophesies, will reign over a kingdom divided over tribal lines, as

opposed to a kingdom divided along any other lines at all, like what job a

person might have or what clothing they may wear.

A

kingdom divided on the basis of tribe and background is a kingdom that we are

living in now, not just a kingdom that Jeroboam reigned over nearly three

thousand years ago. The divided kingdom of Jeroboam is still very much alive

and well, and it is a kingdom that we still live in today.

Yet

on the surface, this ought not be so. The world is more connected than ever—the

news travels quicker, social media keeps us in touch with people literally

around the entire world, and the capacity to reach out to anyone at any time is

literally just a phone call or a text message or an email away from happening.

The iconic image and story of Ieshia Evans traveled across the country

instantly!

But

here we are, still living and dying within Jeroboam’s divided kingdom.

So

try to leave that kingdom behind. Venture outside of it, even if—especially if—it

is your comfort zone. Reach out to someone not in your normal circle of

contacts. Give an ear to someone with a vastly different background or identity

from yours. You don’t have to agree with them, but do try to understand them.

It is what Jesus did when assembling the Twelve—He reached for tax collectors

and zealots alike, and Judean disciples alongside the majority Galilean

disciples—and it is what we should do as well.

Because

if we are going to say that #AllLivesMatter, then we cannot continue to be in

the business of insisting that our leaders, our media, and ourselves be in the

business of sweeping the identity of some lives under the rug.

We

can start to reverse that by being able to see the other, someone who may look

very, very different from us, as being as fearfully and wonderfully made by

God. I don’t have all the answers, but this is, I think, the first answer, and

may the rest come from that one.

May

it be so. Amen.

Rev.

Eric Atcheson

Longview,

Washington

August

21, 2016

Saturday, August 20, 2016

There Is No Christian Case for Trump: A Response to Jerry Falwell Jr.

Oh boy, oh boy. My bete noir (to the extent that I am allowed one in my very humble little slice of the internet's blogosphere), Liberty University chancellor Jerry Falwell Jr., whom I have taken to task here multiple times in the past, just came out with one doozy of a column in the Washington Post explaining why he has endorsed one Donald J. Trump for El Presidente.

I'm used to debating line-by-line from my days as a high school and college debater, so let's break down this smorgasbord of AmeriChristian claptrap down into bite-sized pieces, shall we? Italics are Falwell's words, regular font represents my responses. I promise I have not edited Falwell's words in any way, and have quoted entire thoughts to avoid any removal of context of individual words (but, hey, please check my work if you want--I link to the original column above).

We have lived through nearly eight years of weak leadership from a president who did not sign the charter to create the Islamic State but whose policies had the intended or unintended effect (we will be debating that for decades) of breathing life into the lungs of the terrorist group. President Obama and Hillary Clinton most definitely signaled to Islamic State leaders that they had no intention of seriously challenging them, or even of calling radical Islamic terrorism by its name. Instead, Obama and Clinton pulled our troops out of Iraq, drew and then quickly erased a red line in Syria and tried to convince us that unverifiable pinpoint drone strikes (after leaflet warnings) would win the war against the Islamic State.

We will ignore for a moment the immutable fact that the withdrawal of troops from Iraq was per an agreement that George W. Bush signed as president, and that President Obama simply executed, as well as the fact that in Syria, the war against the Islamic State is being fought by someone just as diabolical: Bashar al-Assad, a feckless strongman more than happy to use weapons of mass destruction against his own citizens.

Set all of those facts aside for a moment. Donald Trump's plan, to the extent that he has prominently articulated one, to address the Islamic State is to bring back torture and to target family members for assassination. His plan is to order US personnel to commit war crimes.

So, Jerry Jr., WWJD? What Would Jesus Do?

I'm willing to bet that the Prince of Peace would eschew committing war crimes. Call it a hunch, it's not like I have any real education in this or anything.

The policies of Obama and Clinton have made the world unstable and unsafe and created a world stage eerily similar to that of the late 1930s. We could be on the precipice of international conflict like nothing we have seen since World War II. Obama and Clinton are the Neville Chamberlains of our time.

It may feel like the late 1930s to you, but you're operating like it's the early 1930s, since you're actually actively trying to get America to elect a candidate who has espoused such Nuremburg-esque ideas like banning an entire religion from the country and using police resources to harass its adherents. Only instead of Adolf Hitler and German Jews, it's Donald Trump and American Muslims. I get it, though, you say "potato."

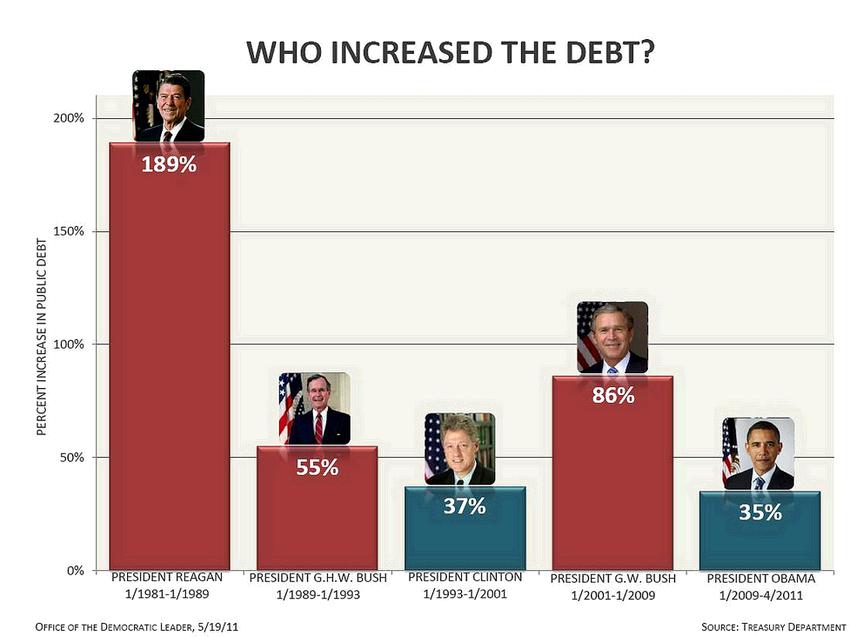

Domestically, Obama and Clinton have pushed to $19 trillion the debt that our children and grandchildren will somehow have to find a way to repay.

I'm just going to leave this graphic here, which the fact-checking site snopes.com rated as "mostly true." You get to reading it at your convenience.

Even our noble law enforcement has been demonized by the Obama administration, and anarchy is erupting in our cities.

You mean demonized like...this? Sure, if you say so.

I chose to personally support Donald Trump for president early on and referred to him as America’s blue-collar billionaire at the Republican National Convention because of his love for ordinary Americans and his kindness, generosity and bold leadership qualities.

And I quote Jon Stewart on "blue-collar billionaire:" That's. Not. A. Thing.

And I quote Jesus on the billionaires of His day: “I assure you that it will be very hard for a rich person to enter the kingdom of heaven. In fact, it’s easier for a camel to squeeze through the eye of a needle than for a rich person to enter God’s kingdom.”

That's from Matthew 19. And it's not even remotely the only condemnatory thing Jesus has to say about wealth and its hoarders.

Also, Trump's generosity, really? This is a guy who used Trump Foundation funds to buy a Tim Tebow helmet for himself. This is a guy who had to be shamed into fulfilling a public promise to give $1 million to veteran causes. This is a guy who is doing something unprecedented in modern presidential politics and refusing to release his tax returns, in part, because it's likely that it will reveal just how little--if any--he does in fact give to charity.

So when you talk about Trump's generosity, I don't know what you're referring to. I suspect neither do an awful lot of other Christians.

We need a leader with qualities that resemble those of Winston Churchill, and I believe that leader is Donald Trump. As Churchill did, Trump possesses the resolve to put his country first and to never give up in a world that is increasingly hostile to our values.

Oh sweet wounded Jesus, where do I begin with this. Churchill may have famously said that democracy is the worst system of government except for all the others (I'm paraphrasing), but he was as anti-fascist as they come, so much so that at one point, he even remarked, "If Hitler invaded Hell, I would at least make a favorable reference to the devil in the House of Commons." Trump, on the other hand, openly praises strongmen like Vladimir Putin and Saddam Hussein, and has been endorsed by North Korean tyrant Kim Jong-Un.

Churchill was genuinely heroic, and though far from a perfect leader--his attitude towards, say, India especially was particularly unenlightened--he is almost certainly spinning in his grave over his name now being associated with a racist, orange-hued gasbag by a chancellor of a university that teaches fake science to its students.

Despite our differences, Americans from all walks of life must unite behind Trump and Indiana Gov. Mike Pence or suffer dire consequences. If Clinton appoints the next few Supreme Court justices, not only will the Second Amendment right to bear arms be effectively lost, but also activist judges will rewrite our Constitution in ways that would make it unrecognizable to our founders.

First, to borrow from Deborah Fikes in the New York Times, what is this Christian obsession with the right to bear arms? "Our evangelical brothers and sisters cannot comprehend that American evangelicals are so overwhelmingly opposed to any gun control reform."

And, to borrow again from Jesus, this time from Matthew 26:52: "Put the sword back in its place. All who use the sword will die by the sword."

If you want to campaign for your right to bear arms, cool, it's a free country. But please don't pretend that campaigning for this right has anything to do with Jesus. It doesn't. I'm fairly certain, in fact, based on the above verse--which He said precisely to prevent His disciples from engaging in self-defense against a tyrannical government (the temple leadership that collaborated with the occupying Roman Empire) that He would be appalled at such an association.

(This, by the by, is on top of what I have to imagine is the antipathy to which a Jesus who repeatedly stood on the side of the poor and the outcast would feel towards a campaign that has repeatedly gotten in trouble over anti-Semitic advisers and tweets. Each and every time, the Trump campaign claims it's not anti-Semitic, but if it looks like a duck and it quacks like a duck...)

And really, that might be the biggest takeaway from this takedown: that there is no Christian case to make for Trump, even though it is a very prominent Christian leader who penned that column to which I have spent the last however-many words responding. Jerry Falwell Jr. is a Christian leader. He is the chancellor of the largest Christian university in the country. His very surname is synonymous with evangelicalism and has been for decades.

And not one jot of what he has to say has a lick to do with making the case for Trump from any semblance of a Christian perspective. It could just as easily have been written by a hardened atheist, with none of the words changed, and nobody would have batted an eye.

Because there isn't any case to make for Trump from a Christian perspective. Jesus Christ was humble, selfless, and a champion of the outcast. Trump is none of these things. He never was. He still isn't. He could be, one day, if by a miracle he had a Paul-on-the-road-to-Damascus moment and was overwhelmed by the grace and glory of God and decided then and there to dedicate himself to genuine Christian living, not to treating Christianity as something to be exploited, to be given promises of power in exchange for its blessing.

But that hasn't happened yet. And until it does--and if it doesn't ever--then I strongly suspect that Jerry Falwell Jr. and Christian leaders who are acting like him right now, will be confronted by an extraordinarily disappointed God at judgment, who will demand an explanation from them as to why they chose to do the fervently un-Christlike thing in endorsing a race-baiting, xenophobic, vulgar, sexist, womanizing bigot for president of the most powerful country on God's creation.

Vancouver, Washington

August 20, 2016

Presidential debt graphic courtesy of snopes.com, cartoon courtesy of blogspot.com

I'm used to debating line-by-line from my days as a high school and college debater, so let's break down this smorgasbord of AmeriChristian claptrap down into bite-sized pieces, shall we? Italics are Falwell's words, regular font represents my responses. I promise I have not edited Falwell's words in any way, and have quoted entire thoughts to avoid any removal of context of individual words (but, hey, please check my work if you want--I link to the original column above).

We have lived through nearly eight years of weak leadership from a president who did not sign the charter to create the Islamic State but whose policies had the intended or unintended effect (we will be debating that for decades) of breathing life into the lungs of the terrorist group. President Obama and Hillary Clinton most definitely signaled to Islamic State leaders that they had no intention of seriously challenging them, or even of calling radical Islamic terrorism by its name. Instead, Obama and Clinton pulled our troops out of Iraq, drew and then quickly erased a red line in Syria and tried to convince us that unverifiable pinpoint drone strikes (after leaflet warnings) would win the war against the Islamic State.

We will ignore for a moment the immutable fact that the withdrawal of troops from Iraq was per an agreement that George W. Bush signed as president, and that President Obama simply executed, as well as the fact that in Syria, the war against the Islamic State is being fought by someone just as diabolical: Bashar al-Assad, a feckless strongman more than happy to use weapons of mass destruction against his own citizens.

Set all of those facts aside for a moment. Donald Trump's plan, to the extent that he has prominently articulated one, to address the Islamic State is to bring back torture and to target family members for assassination. His plan is to order US personnel to commit war crimes.

So, Jerry Jr., WWJD? What Would Jesus Do?

I'm willing to bet that the Prince of Peace would eschew committing war crimes. Call it a hunch, it's not like I have any real education in this or anything.

The policies of Obama and Clinton have made the world unstable and unsafe and created a world stage eerily similar to that of the late 1930s. We could be on the precipice of international conflict like nothing we have seen since World War II. Obama and Clinton are the Neville Chamberlains of our time.

It may feel like the late 1930s to you, but you're operating like it's the early 1930s, since you're actually actively trying to get America to elect a candidate who has espoused such Nuremburg-esque ideas like banning an entire religion from the country and using police resources to harass its adherents. Only instead of Adolf Hitler and German Jews, it's Donald Trump and American Muslims. I get it, though, you say "potato."

Domestically, Obama and Clinton have pushed to $19 trillion the debt that our children and grandchildren will somehow have to find a way to repay.

I'm just going to leave this graphic here, which the fact-checking site snopes.com rated as "mostly true." You get to reading it at your convenience.

Even our noble law enforcement has been demonized by the Obama administration, and anarchy is erupting in our cities.

You mean demonized like...this? Sure, if you say so.

I chose to personally support Donald Trump for president early on and referred to him as America’s blue-collar billionaire at the Republican National Convention because of his love for ordinary Americans and his kindness, generosity and bold leadership qualities.

And I quote Jon Stewart on "blue-collar billionaire:" That's. Not. A. Thing.

And I quote Jesus on the billionaires of His day: “I assure you that it will be very hard for a rich person to enter the kingdom of heaven. In fact, it’s easier for a camel to squeeze through the eye of a needle than for a rich person to enter God’s kingdom.”

That's from Matthew 19. And it's not even remotely the only condemnatory thing Jesus has to say about wealth and its hoarders.

Also, Trump's generosity, really? This is a guy who used Trump Foundation funds to buy a Tim Tebow helmet for himself. This is a guy who had to be shamed into fulfilling a public promise to give $1 million to veteran causes. This is a guy who is doing something unprecedented in modern presidential politics and refusing to release his tax returns, in part, because it's likely that it will reveal just how little--if any--he does in fact give to charity.

So when you talk about Trump's generosity, I don't know what you're referring to. I suspect neither do an awful lot of other Christians.

We need a leader with qualities that resemble those of Winston Churchill, and I believe that leader is Donald Trump. As Churchill did, Trump possesses the resolve to put his country first and to never give up in a world that is increasingly hostile to our values.

Oh sweet wounded Jesus, where do I begin with this. Churchill may have famously said that democracy is the worst system of government except for all the others (I'm paraphrasing), but he was as anti-fascist as they come, so much so that at one point, he even remarked, "If Hitler invaded Hell, I would at least make a favorable reference to the devil in the House of Commons." Trump, on the other hand, openly praises strongmen like Vladimir Putin and Saddam Hussein, and has been endorsed by North Korean tyrant Kim Jong-Un.

Churchill was genuinely heroic, and though far from a perfect leader--his attitude towards, say, India especially was particularly unenlightened--he is almost certainly spinning in his grave over his name now being associated with a racist, orange-hued gasbag by a chancellor of a university that teaches fake science to its students.

Despite our differences, Americans from all walks of life must unite behind Trump and Indiana Gov. Mike Pence or suffer dire consequences. If Clinton appoints the next few Supreme Court justices, not only will the Second Amendment right to bear arms be effectively lost, but also activist judges will rewrite our Constitution in ways that would make it unrecognizable to our founders.

First, to borrow from Deborah Fikes in the New York Times, what is this Christian obsession with the right to bear arms? "Our evangelical brothers and sisters cannot comprehend that American evangelicals are so overwhelmingly opposed to any gun control reform."

And, to borrow again from Jesus, this time from Matthew 26:52: "Put the sword back in its place. All who use the sword will die by the sword."

If you want to campaign for your right to bear arms, cool, it's a free country. But please don't pretend that campaigning for this right has anything to do with Jesus. It doesn't. I'm fairly certain, in fact, based on the above verse--which He said precisely to prevent His disciples from engaging in self-defense against a tyrannical government (the temple leadership that collaborated with the occupying Roman Empire) that He would be appalled at such an association.

(This, by the by, is on top of what I have to imagine is the antipathy to which a Jesus who repeatedly stood on the side of the poor and the outcast would feel towards a campaign that has repeatedly gotten in trouble over anti-Semitic advisers and tweets. Each and every time, the Trump campaign claims it's not anti-Semitic, but if it looks like a duck and it quacks like a duck...)

And really, that might be the biggest takeaway from this takedown: that there is no Christian case to make for Trump, even though it is a very prominent Christian leader who penned that column to which I have spent the last however-many words responding. Jerry Falwell Jr. is a Christian leader. He is the chancellor of the largest Christian university in the country. His very surname is synonymous with evangelicalism and has been for decades.

And not one jot of what he has to say has a lick to do with making the case for Trump from any semblance of a Christian perspective. It could just as easily have been written by a hardened atheist, with none of the words changed, and nobody would have batted an eye.

Because there isn't any case to make for Trump from a Christian perspective. Jesus Christ was humble, selfless, and a champion of the outcast. Trump is none of these things. He never was. He still isn't. He could be, one day, if by a miracle he had a Paul-on-the-road-to-Damascus moment and was overwhelmed by the grace and glory of God and decided then and there to dedicate himself to genuine Christian living, not to treating Christianity as something to be exploited, to be given promises of power in exchange for its blessing.

But that hasn't happened yet. And until it does--and if it doesn't ever--then I strongly suspect that Jerry Falwell Jr. and Christian leaders who are acting like him right now, will be confronted by an extraordinarily disappointed God at judgment, who will demand an explanation from them as to why they chose to do the fervently un-Christlike thing in endorsing a race-baiting, xenophobic, vulgar, sexist, womanizing bigot for president of the most powerful country on God's creation.

Vancouver, Washington

August 20, 2016

Presidential debt graphic courtesy of snopes.com, cartoon courtesy of blogspot.com

Wednesday, August 17, 2016

Dear Longview: You're Not Colorblind. Please Stop Acting Like You Are.

This morning, a police officer shot and killed an African-American man at a gas station in Kelso, the town directly adjoining Longview, where my parish is. Details are still emerging, but it appears the man attacked the officer with a walking stick after similarly attacking the gas station attendants, at which point the officer shot and killed the man.

This post isn't about whether or not shooting the man was justified. So few details are known that any attempt to weigh that decision would, on my part, be a rush to judgment. For instance, I have no way of knowing yet what, if any, bodycam or CCTV footage of the attack might exist, or of any other witnesses who may come forward. So we don't know yet exactly what happened.

No, this post is about the immediate reaction from the Longview-Kelso community, which was galling to say the least. Here is a sampling of comments from Facebook, unedited by me in any way (names redacted to protect the privacy of the not-so-innocent):

good emphasis on the persons color... really Lauren??? SMH

There was NO REASON to state the skin color of the man shot !!! Bad taste on your part Lauren Bkronebush !!!!

Way to go TDN. Play into the mainstream media that everything is race driven. Hopefully the BLM stays out of the area.

Did you HAVE to say black man? Let's get real!

Apparently it's mandatory to state skin color and play into the race baiting. If it had been a white guy I'll bet his race would not have even been mentioned, but since he was black, it's the first thing the article states

Shot and killed a "black man" way to go TDN. If it had been a white man would you have reported that? I doubt it. It's ok everyone knows TDN blows dick and will do whatever possible to sell garbage.

Maybe this just goes to show: never read the comments section. But this is my community, which I love and have invested myself wholly in, so I did.

And man, it's depressing. First, despite all the #BlueLivesMatter talk, I didn't see a single comment (initally, at least--as more comments roll in, that's changing) expressing even a jot of concern for the condition of the officer, who had to be taken to the hospital for treatment. I mean, if we're people first, as other comments suggest, then lets act like people and actually be concerned for someone who was physically attacked to the point of hospitalization instead of screaming at a newspaper in an effort to defend our inability to understand race.

I'm not sure we can, though, or will, because these comments are among the ones with the most likes on the Facebook page linking the story, too. I'm sure there will be letters to the editor as well reflecting this sentiment. So do we really care about #BlueLivesMatter, or do we simply care about erasing blackness?

Because that would be a sentiment that is unnervingly unaware of our context. Longview as a town has next to no racial diversity to begin with--Cowlitz County, according to 2015 US census data, is 0.9% African-American, 2.0% Native American, 8.6% Hispanic or Latino/a, and 2.1% Asian-American, Hawaiian, or Pacific Islander. We're nearly 89% white.

That matters. That high level of homogeneity leads to racism even when we claim to be colorblind. A few weeks ago in a Sunday sermon, I conveyed how I had been mistakenly (and not in a good way) taken for an Arab Muslim. The same newspaper being slammed in the comments section has also printed multiple racist letters to the editor from various citizens. I've heard racial slurs and jokes used in casual conversation multiple times. So has my wife, to the point that we won't patronize certain businesses in town because after living here for five years (me) and two years (Carrie), we now know that they are run by racists.

Ironically, I would imagine that many of the same people who are making these comments now, or have written those letters, or have made those jokes and comments, are similarly opposed to "political correctness" as an awful bit of pandering to special little snowflakes who get offended over how race is discussed in America today.

Except that's exactly what you're doing now. You're getting offended over how race is being discussed--by a news reporter, in this case--and are demanding to be pandered to as a result of your sensitive sensibilities being so grievously offended.

So stop saying you're colorblind, or that color doesn't matter. Color absolutely matters. Maybe you think it doesn't because you don't have any friends of color, but if that's the case, ask yourself why that is.

Please ask yourselves why you are so content living in a social world you have made for yourself that is so uniform.

Please ask yourselves why you so desperately want a news reporter to censor a salient detail from a breaking, tragic story when the point of the news is to, well, report those salient details.

Please ask yourselves why a serial liar and adulterer with no relevant experience managed to earn the presidential nomination of a major party largely by appealing to racism, jingoism, and nativism.

Please ask yourselves why it is an immutable statistical reality that people of color are in fact more likely to be shot and killed by law enforcement, are more likely to be sentenced to death in the legal system, and are more likely to be sentenced to life in prison under three-strikes laws than whites.

And finally, please ask yourselves just how outraged you would be if it was your family, and your friends, facing down that sort of deadly statistical reality of your very existence. Please ask yourselves how much you would be willing to move heaven and earth to express that outrage, and how much pain it might cause to see others demand that your identity be erased from news stories like this one.

None of that says you are colorblind. Quite the contrary. So please stop acting like you are. Please show some empathy for your brothers and sisters of color. Say a prayer for them, reach out to them, do something proactive and constructive.And if you don't have any brothers and sisters of color...maybe try to purposely work on changing that in a positive way.

I offer all that advice as a pastor who has been embedded in this community for five years and, despite my criticism here, this is a community I still love and treasure. I want to see it, and us, do better than the comments I am reading and shaking at now.

So let's do better, then. Together.

Thanks for reading.

This post isn't about whether or not shooting the man was justified. So few details are known that any attempt to weigh that decision would, on my part, be a rush to judgment. For instance, I have no way of knowing yet what, if any, bodycam or CCTV footage of the attack might exist, or of any other witnesses who may come forward. So we don't know yet exactly what happened.

No, this post is about the immediate reaction from the Longview-Kelso community, which was galling to say the least. Here is a sampling of comments from Facebook, unedited by me in any way (names redacted to protect the privacy of the not-so-innocent):

good emphasis on the persons color... really Lauren??? SMH

There was NO REASON to state the skin color of the man shot !!! Bad taste on your part Lauren Bkronebush !!!!

Way to go TDN. Play into the mainstream media that everything is race driven. Hopefully the BLM stays out of the area.

Did you HAVE to say black man? Let's get real!

Apparently it's mandatory to state skin color and play into the race baiting. If it had been a white guy I'll bet his race would not have even been mentioned, but since he was black, it's the first thing the article states

Shot and killed a "black man" way to go TDN. If it had been a white man would you have reported that? I doubt it. It's ok everyone knows TDN blows dick and will do whatever possible to sell garbage.

Maybe this just goes to show: never read the comments section. But this is my community, which I love and have invested myself wholly in, so I did.

And man, it's depressing. First, despite all the #BlueLivesMatter talk, I didn't see a single comment (initally, at least--as more comments roll in, that's changing) expressing even a jot of concern for the condition of the officer, who had to be taken to the hospital for treatment. I mean, if we're people first, as other comments suggest, then lets act like people and actually be concerned for someone who was physically attacked to the point of hospitalization instead of screaming at a newspaper in an effort to defend our inability to understand race.

I'm not sure we can, though, or will, because these comments are among the ones with the most likes on the Facebook page linking the story, too. I'm sure there will be letters to the editor as well reflecting this sentiment. So do we really care about #BlueLivesMatter, or do we simply care about erasing blackness?

Because that would be a sentiment that is unnervingly unaware of our context. Longview as a town has next to no racial diversity to begin with--Cowlitz County, according to 2015 US census data, is 0.9% African-American, 2.0% Native American, 8.6% Hispanic or Latino/a, and 2.1% Asian-American, Hawaiian, or Pacific Islander. We're nearly 89% white.

That matters. That high level of homogeneity leads to racism even when we claim to be colorblind. A few weeks ago in a Sunday sermon, I conveyed how I had been mistakenly (and not in a good way) taken for an Arab Muslim. The same newspaper being slammed in the comments section has also printed multiple racist letters to the editor from various citizens. I've heard racial slurs and jokes used in casual conversation multiple times. So has my wife, to the point that we won't patronize certain businesses in town because after living here for five years (me) and two years (Carrie), we now know that they are run by racists.

Ironically, I would imagine that many of the same people who are making these comments now, or have written those letters, or have made those jokes and comments, are similarly opposed to "political correctness" as an awful bit of pandering to special little snowflakes who get offended over how race is discussed in America today.

Except that's exactly what you're doing now. You're getting offended over how race is being discussed--by a news reporter, in this case--and are demanding to be pandered to as a result of your sensitive sensibilities being so grievously offended.

So stop saying you're colorblind, or that color doesn't matter. Color absolutely matters. Maybe you think it doesn't because you don't have any friends of color, but if that's the case, ask yourself why that is.

Please ask yourselves why you are so content living in a social world you have made for yourself that is so uniform.

Please ask yourselves why you so desperately want a news reporter to censor a salient detail from a breaking, tragic story when the point of the news is to, well, report those salient details.

Please ask yourselves why a serial liar and adulterer with no relevant experience managed to earn the presidential nomination of a major party largely by appealing to racism, jingoism, and nativism.

Please ask yourselves why it is an immutable statistical reality that people of color are in fact more likely to be shot and killed by law enforcement, are more likely to be sentenced to death in the legal system, and are more likely to be sentenced to life in prison under three-strikes laws than whites.

And finally, please ask yourselves just how outraged you would be if it was your family, and your friends, facing down that sort of deadly statistical reality of your very existence. Please ask yourselves how much you would be willing to move heaven and earth to express that outrage, and how much pain it might cause to see others demand that your identity be erased from news stories like this one.

None of that says you are colorblind. Quite the contrary. So please stop acting like you are. Please show some empathy for your brothers and sisters of color. Say a prayer for them, reach out to them, do something proactive and constructive.And if you don't have any brothers and sisters of color...maybe try to purposely work on changing that in a positive way.

I offer all that advice as a pastor who has been embedded in this community for five years and, despite my criticism here, this is a community I still love and treasure. I want to see it, and us, do better than the comments I am reading and shaking at now.

So let's do better, then. Together.

Thanks for reading.

Tuesday, August 16, 2016

My Faustian Bargain

Celexa.

Prozac.

Wellbutrin.

Trileptal.

Effexor.

Seven years ago, the minute my Clinical Pastoral Education internship as a hospital chaplain in San Francisco was up, I made an appointment with a psychiatrist in Berkeley. I had managed to live functionally without being medicated since moving to Berkeley a year prior to begin seminary, but my major clinical depression roared back with such a vengeance in years two and three that I had to return to the care of a psychiatrist, and have remained treated and medicated every day since.

Except the medications themselves hardly made matters easy. Celexa, the antidepressant I was prescribed as a teenager, now produced severe mood swings in me, and I remained on it only a matter of weeks. I was happily on a combination of Prozac and Wellbutrin for years, until side effects with that combination likewise proved to be a significant obstacle.

Because a number of physical and sexual side effects are common to the family of medications Prozac belongs to, known as SSRIs, my psychiatrist recommended switching me to an SNRI anti-depressant, and thus began my now-two-year-old relationship with Effexor.

With Effexor, I can live, function, and work without any side effects to the drug that keeps me sane, but only if I take it at precise 24-hour intervals. Effexor has by far the shortest half-life of most common antidepressants, and I'm a pretty big chap. If I forgot a day, by the next morning like clockwork, I would be laid out but good with dizzy spells, vertigo, and nausea.

Lately, I haven't even had to forget a day--just take a dose later than I had the previous day. Which is why I'm sitting here on the couch at home, writing this in between dizzy spells, to quite simply say, on behalf of all of us who do suffer from mental illness:

It isn't always the illness that you see affect people. Sometimes it's the treatment.

Think of chemotherapy. The side effects you associate with cancer patients--the loss of hair, the emaciated figure, those come from the treatment, not necessarily the illness. Chemo can save a cancer patient's life, but enough of it would almost certainly kill them as well.

Antidepressants can have the same effect, albeit in a much less extreme way, in that sometimes, the symptoms are from the medicine, not the illness it is treating.

I remember when, while in seminary, the HIV+ pastor of the church plant I was worshiping at shared that he had to go on a new regimen of drugs, and one would likely either cause some weight gain while another would adversely affect the quality of his sleep. Either symptom would result in visible outward signs, but not from the far more dangerous disease the medication would be fighting.

It is a Faustian bargain we make with our treatments, because while we know they work, we also know what else such potent cocktails are capable of doing. When I take my Effexor at exact intervals, I can live symptom-free with my depression treated, which is something I quite simply have never been able to say with another medication.

But if I miss a dose? Woe be to my equilibrium and sense of stasis.

So, on a rare day when the side effects of my medication are rearing their ugly head, I felt it important to say this:

This reality is why, even though I have been under no obligation to do so, I have revealed my diagnosis to church committees and pastors who have considered hiring me in previous search processes before any vote was taken. Not because they should discriminate on the basis of mental health--they shouldn't--but because it is possible for not only my diagnosis but my cure to adversely impact my ability to work, even if only for a few hours at a time, especially considering that solo pastors in particular are functionally on call 24/7.

Fortunately, I can work from home most days of the week--much more than I actually do. I usually only work from home on Wednesdays, which is my sermon writing day--I need as much control over my writing time as possible, and the distractions of ringing phones and visitors at my office tend to detract from that. But if I wanted to work from home two days a week, I really very easily could--I could still keep office hours two days a week while combining my home/hospital visitations with excursions for coffee, lunch, or meetings.

But not everyone else has that luxury. So, if you see someone else who has made a similar bargain with the medications that keep them sane or alive, please, show some patience and some humility in the face of what is for them sometimes a daily struggle. And if you have someone in your life for whom that is the case, I promise that the good karma you are reaping for walking alongside that person does not, and will not, go to waste.

Vancouver, Washington

August 16, 2016

Image of the structural formula of venlafaxine (Effexor) from Wikipedia.

Prozac.

Wellbutrin.

Trileptal.

Effexor.

Seven years ago, the minute my Clinical Pastoral Education internship as a hospital chaplain in San Francisco was up, I made an appointment with a psychiatrist in Berkeley. I had managed to live functionally without being medicated since moving to Berkeley a year prior to begin seminary, but my major clinical depression roared back with such a vengeance in years two and three that I had to return to the care of a psychiatrist, and have remained treated and medicated every day since.

Except the medications themselves hardly made matters easy. Celexa, the antidepressant I was prescribed as a teenager, now produced severe mood swings in me, and I remained on it only a matter of weeks. I was happily on a combination of Prozac and Wellbutrin for years, until side effects with that combination likewise proved to be a significant obstacle.

Because a number of physical and sexual side effects are common to the family of medications Prozac belongs to, known as SSRIs, my psychiatrist recommended switching me to an SNRI anti-depressant, and thus began my now-two-year-old relationship with Effexor.

With Effexor, I can live, function, and work without any side effects to the drug that keeps me sane, but only if I take it at precise 24-hour intervals. Effexor has by far the shortest half-life of most common antidepressants, and I'm a pretty big chap. If I forgot a day, by the next morning like clockwork, I would be laid out but good with dizzy spells, vertigo, and nausea.

Lately, I haven't even had to forget a day--just take a dose later than I had the previous day. Which is why I'm sitting here on the couch at home, writing this in between dizzy spells, to quite simply say, on behalf of all of us who do suffer from mental illness:

It isn't always the illness that you see affect people. Sometimes it's the treatment.

Think of chemotherapy. The side effects you associate with cancer patients--the loss of hair, the emaciated figure, those come from the treatment, not necessarily the illness. Chemo can save a cancer patient's life, but enough of it would almost certainly kill them as well.

Antidepressants can have the same effect, albeit in a much less extreme way, in that sometimes, the symptoms are from the medicine, not the illness it is treating.

I remember when, while in seminary, the HIV+ pastor of the church plant I was worshiping at shared that he had to go on a new regimen of drugs, and one would likely either cause some weight gain while another would adversely affect the quality of his sleep. Either symptom would result in visible outward signs, but not from the far more dangerous disease the medication would be fighting.

It is a Faustian bargain we make with our treatments, because while we know they work, we also know what else such potent cocktails are capable of doing. When I take my Effexor at exact intervals, I can live symptom-free with my depression treated, which is something I quite simply have never been able to say with another medication.

But if I miss a dose? Woe be to my equilibrium and sense of stasis.

So, on a rare day when the side effects of my medication are rearing their ugly head, I felt it important to say this:

This reality is why, even though I have been under no obligation to do so, I have revealed my diagnosis to church committees and pastors who have considered hiring me in previous search processes before any vote was taken. Not because they should discriminate on the basis of mental health--they shouldn't--but because it is possible for not only my diagnosis but my cure to adversely impact my ability to work, even if only for a few hours at a time, especially considering that solo pastors in particular are functionally on call 24/7.

Fortunately, I can work from home most days of the week--much more than I actually do. I usually only work from home on Wednesdays, which is my sermon writing day--I need as much control over my writing time as possible, and the distractions of ringing phones and visitors at my office tend to detract from that. But if I wanted to work from home two days a week, I really very easily could--I could still keep office hours two days a week while combining my home/hospital visitations with excursions for coffee, lunch, or meetings.

But not everyone else has that luxury. So, if you see someone else who has made a similar bargain with the medications that keep them sane or alive, please, show some patience and some humility in the face of what is for them sometimes a daily struggle. And if you have someone in your life for whom that is the case, I promise that the good karma you are reaping for walking alongside that person does not, and will not, go to waste.

Vancouver, Washington

August 16, 2016

Image of the structural formula of venlafaxine (Effexor) from Wikipedia.

Sunday, August 14, 2016

This Week's Sermon: "The Lord Raised"

1 Kings 11:14-25

14 So the Lord raised up an opponent for Solomon: Hadad the Edomite from the royal line of Edom. 15 When David was fighting against Edom, Joab the general had gone up to bury the Israelite dead, and he had killed every male in Edom. 16 Joab and all the Israelites stayed there six months, until he had finished off every male in Edom. 17 While still a youth, Hadad escaped to Egypt along with his father’s Edomite officials. 18 They set out from Midian and went to Paran. They took men with them from Paran and came to Egypt and to Pharaoh its king. Pharaoh assigned him a home, food, and land.

19 Pharaoh was so delighted with Hadad that he gave him one of his wife’s sisters for marriage, a sister of Queen Tahpenes. 20 This sister of Tahpenes bore Hadad a son, Genubath. Tahpenes weaned him in Pharaoh’s house. So it was that Genubath was raised in Pharaoh’s house, among Pharaoh’s children. 21 While in Egypt, Hadad heard that David had lain down with his ancestors and that Joab the general was also dead. Hadad said to Pharaoh, “Let me go to my homeland.” 22 Pharaoh said to him, “What do you lack here with me that would make you want to go back to your homeland?” Hadad said, “Nothing, but please let me go!”

23 God raised up another opponent for Solomon: Rezon, Eliada’s son, who had escaped from Zobah’s King Hadadezer. 24 Rezon recruited men and became leader of a band when David was killing them. They went to Damascus, stayed there, and ruled it. 25 Throughout Solomon’s lifetime, Rezon was Israel’s opponent and added to the problems caused by Hadad. Rezon hated Israel while he ruled as king of Aram. (Common English Bible)

14 So the Lord raised up an opponent for Solomon: Hadad the Edomite from the royal line of Edom. 15 When David was fighting against Edom, Joab the general had gone up to bury the Israelite dead, and he had killed every male in Edom. 16 Joab and all the Israelites stayed there six months, until he had finished off every male in Edom. 17 While still a youth, Hadad escaped to Egypt along with his father’s Edomite officials. 18 They set out from Midian and went to Paran. They took men with them from Paran and came to Egypt and to Pharaoh its king. Pharaoh assigned him a home, food, and land.

19 Pharaoh was so delighted with Hadad that he gave him one of his wife’s sisters for marriage, a sister of Queen Tahpenes. 20 This sister of Tahpenes bore Hadad a son, Genubath. Tahpenes weaned him in Pharaoh’s house. So it was that Genubath was raised in Pharaoh’s house, among Pharaoh’s children. 21 While in Egypt, Hadad heard that David had lain down with his ancestors and that Joab the general was also dead. Hadad said to Pharaoh, “Let me go to my homeland.” 22 Pharaoh said to him, “What do you lack here with me that would make you want to go back to your homeland?” Hadad said, “Nothing, but please let me go!”

23 God raised up another opponent for Solomon: Rezon, Eliada’s son, who had escaped from Zobah’s King Hadadezer. 24 Rezon recruited men and became leader of a band when David was killing them. They went to Damascus, stayed there, and ruled it. 25 Throughout Solomon’s lifetime, Rezon was Israel’s opponent and added to the problems caused by Hadad. Rezon hated Israel while he ruled as king of Aram. (Common English Bible)

“The Dreaming Architect:

Solomon, Son of David & Bathsheba, King of Israel,” Week Nine

You

may think that my generation, the millennials, is the worst. After all, we text

too much, we listen to terrible music, and we singlehandedly killed off

penmanship. We’re basically one Woodstock away from being utterly beyond help.

But

consider this: down in Rio de Janeiro, five millennial American women just

turned in perhaps the most dominant team performance in gymnastics in Olympic

history. Another American millennial just won his 20th Olympic gold

medal. Still yet another just shattered the world record by so far that her opponents couldn't even be seen on-screen when she won. And one of those annoying, horrible things we use our phones constantly

for—the taking of selfies—is actually giving the world a glimmer of hope in one

of the most fraught conflicts of our time.

A

17-year-old South Korean gymnast, Lee Eun-ju, smiled and flashed the universal

two-fingered peace sign alongside one of her North Korean gymnast counterparts,

Hong Un-jong, who leaned in and smiled next to an athletic representative of a

country that hers is technically still at war with, stretching all the way back

to 1950.

Even

as international politics remain tense between the two Koreas—and despite

claims from the belligerent, despotic North that they do indeed still want

reunification—two young women were presented with a choice to make as to how to

approach their historic rival. They could have chosen civility, apathy, or even

outright hostility. But they chose joy, and celebration of one another in a

memento that will be, I can well imagine, treasured for a long time by them,

and that has already been treasured by millions on social media.

How

we react when presented with a potential rival, it says a lot about who we are,

and about the fundamental nature of our character. God raised up rivals for

Solomon as a result of the Israelite king’s straying from the path and covenant

of God, and how we might react to such rivals ourselves is the question that we

face today—and that athletes from various warring nations are as well in Rio.

This

is a summer sermon series in the mold of one that, stylistically, just like a

couple of years ago in 2014, when, if you’ll remember, we spent most of the

summer reading verse-by-verse through the beginning of Acts, we have once more

taken on one big narrative in Scripture.

Only

this time, that narrative has been the life and reign of King Solomon, a

fascinating figure in Israelite history who has probably been somewhat

mythologized and made into a King Arthur-esque national legend over the years,

but who nonetheless represents an epoch centered around a singular truth that

was not achieved again for hundreds of years, and then again for thousands:

ruling over Israel as a unified and independent kingdom.

Believe

it or not, a unified and independent Israel is a rarity in history. After

Solomon, an independent and unified Israel would only really exist twice:

during the short reign of the Maccabees (of whom you have probably heard via

the Hanukkah story), and during present history since 1946.

So

Solomon’s reign—and his father David’s before him—is unique. How Solomon is

remembered matters because of it. And we’ve gotten a chance to read this

dreaming architect’s story from his building of the original temple in

Jerusalem after receiving divine wisdom from the Lord in the dream all the way

up to today’s story of the visit from the queen of Sheba, which represented in

many ways the absolute pinnacle for Solomon and his reign, to today’s story

just one chapter later, in which we continue to see how the seeds of Solomon’s

spiritual and political downfall were sown after last week’s story of God

telling Solomon basically as such, except that here, the theology seems almost

retconned into the rivalries.

By

that I mean: Solomon is at this point in the narrative an old man, but the two

rivals described here—Hadad and Rezon—seem to have been set against Solomon for

quite some time now, as the text says, “Throughout Solomon’s lifetime, Rezon

was Israel’s opponent.” This creates two key distinctions between the

opposition of Jeroboam, who we’ll see next week, and the opposition of Hadad

and Rezon: the latter two represent foreign threats to Solomon’s power, while

Jeroboam represents a domestic threat. And second, Jeroboam used to work for

Solomon as, basically, Solomon’s chief slave overseer, so this conflict with

Jeroboam was likely much newer than the conflicts with Hadad and Rezon, even

though these two only come into the Scriptures now.

The

simplest way to approach this is to suppose that this conflict had existed for

many years, and was retroactively given divine dimensions once Solomon began to

stray from God. And if your agenda is to paint a picture, as the author of 1

Kings has done, of Solomon as an extraordinary king prior to his fall, then

including just how fierce his foreign rivals were wouldn’t quite be the way to

do it if the king had seemingly failed to completely contain those rivals.

It

suggests that whatever steps Solomon may have taken to address Hadad and

Rezon—we do not know what they are, as the author does not tell us—simply were

not enough, or not the right steps to take. Which would represent quite an

error for a king who was praised earlier, via the stories of King Hiram of Tyre

and the Queen of Sheba, as well as having seven hundred wives mostly sealed

through various alliances, for being an exceptionally talented diplomat.

Perhaps

that should be no fault of Solomon’s—after all, Hadad is a refugee from what

was basically a genocide in Edom under David’s disgraced army commander, Joab,

and Rezon also seems irretrievably antagonistic towards Solomon’s Israel—but

even towards an enemy, what you choose to do, or not do, and say, or not say,

matters. If you think it doesn’t, just look at the joyous reception that the

selfie of two Korean gymnasts has received all around a world that is battered

to the point of breaking by hatred and violence.

Those

are the responses towards a rival that we need, and that God wants, of us. If

the Lord has raised a rival for us, that isn’t to mean that God is somehow so

much of a micromanager that God wants to see if we’ll pass the test, no.

God

already knows that we are capable of passing the test of how we treat our

opponents. God doesn’t need to see if we are or not. This isn’t about God

testing us simply because God can. God isn’t so needy and emotionally

vindictive for that.

No,

this is about how we test ourselves, and how we respond. God may raise rivals

for us, but it is up to us whether those rivalries are re-entrenched or not,

become stronger or not, or even become more violent or not. All of those

outcomes are entirely up to us, whether we choose to admit that we have that

sort of capacity or not. What we cannot do is simply chalk it all up to “God’s

plan,” as though God’s master to-do list somehow absolves us of responsibility.

No, God may have raised up Hadad and Rezon as rivals, but whether they stayed

rivals was up to Solomon, and Solomon alone.

You

may not have rivals on the global scale that ancient kings or modern gymnasts

do, but the lack of breadth in a rivalry should not be mistaken for a lack of

depth. You may well have someone who you do see as opposing you, whether in

work or in your personal relationships, someone who simply seems to not want

what you have to bring to the table.

I’m

not saying that God put that person there for you. But I am saying that God

will know how you choose to respond to that person, for good or for bad. Do you

go for the jugular because that’s all you know from the evil within you and

within the world, and it’s awfully tempting and temporarily satisfying to do

(trust me, I know—it’s one of my peccadilloes too)?

That

is what another athlete at the Rio Olympics did—an Egyptian competitor in judo

who refused to shake his opponent’s hand because his opponent was Israeli. The

lack of sportsmanship prompted boos and widespread criticism, and

understandably so.

So