9 Love should be shown without pretending. Hate evil, and hold on to what is good. 10 Love each other like the members of your family. Be the best at showing honor to each other. 11 Don’t hesitate to be enthusiastic—be on fire in the Spirit as you serve the Lord! 12 Be happy in your hope, stand your ground when you’re in trouble, and devote yourselves to prayer. 13 Contribute to the needs of God’s people, and welcome strangers into your home. 14 Bless people who harass you—bless and don’t curse them. 15 Be happy with those who are happy, and cry with those who are crying. 16 Consider everyone as equal, and don’t think that you’re better than anyone else. Instead, associate with people who have no status. Don’t think that you’re so smart. 17 Don’t pay back anyone for their evil actions with evil actions, but show respect for what everyone else believes is good. 18 If possible, to the best of your ability, live at peace with all people. (Common English Bible)

“The Marks

of a True Christian,” Romans 12:9-18

The ballplayer and the journalist enjoyed an

incredibly rich friendship together—uncommon, considering that journalists aren’t

really supposed to get too attached to the subjects they write about, you know,

ethically speaking, in order to maintain their objectivity. But Joe Posnanski couldn’t help but be

attached to Buck O’Neil—nobody could, really.

Buck O’Neil was part of the heart and soul of the Negro Leagues all the

way back in the ‘30s and ‘40s, before Jackie Robinson broke the almighty color

barrier in 1947, and he broke a color barrier himself—in 1962, the Chicago Cubs

hired Buck as the first coach of color in the major leagues. Buck was up for admittance to the Baseball Hall

of Fame in Cooperstown in 2006 as a part of a special, one-time vote for Negro

Leagues ballplayers and managers, and he just missed the cut.

Rather than be bitter at his exclusion, he

instead traveled to Cooperstown and spoke at the inclusion of the other

seventeen who had made it, and as part of his speech, he led the assembled

crowd in a simple sung refrain: “The greatest thing in all my life is loving

you.”

Buck O’Neil died less than three months later.

This year, Joe Posnanski—the sportswriter—wrote

about his friendship with Buck, and this is one of the several anecdotes he shared:

We were in

Houston, at a ballgame, and I saw a man steal a foul ball from a boy. It was flagrant—the man just took the ball

right away from the boy, and he held it up high like it was the head of Medusa,

and I said: “Would you look at this jerk?”

“What’s

that?” Buck said.

“That guy

down there, he just took that ball away from that kid.”

Buck

considered the situation. He said, “Don’t

be so hard on him. He might have a kid

of his own at home.”

“Wait a

minute,” I said to Buck. “If he’s got a

kid, why didn’t he bring him to the ballgame?”

I smiled

triumphantly. But Buck did not hesitate.

“Maybe,” he

said, “the kid is sick.”

Okay, probably the guy didn’t have a sick kid at

home, but isn’t it remarkable that someone who has been around as long as, say,

Buck O’Neil has (and who has experienced the kind of racism that Buck would

have in the US in, say, the 1930’s) does not give into that immediate cynicism

and rather tries to see the entire person behind the action, not out of

gullibility but out of real, authentic goodness?

That is a mark of a true person. It is a mark, I think, that Paul would say

here in Romans 12 is of a true Christian.

And that is what we are going to be talking about today, in the sermon I

auctioned off as a part of our silent auction back in July, which was won by

Shanae Strite! Shanae asked me for a

sermon on Romans 12, but with a specific eye towards how we do not act in the

ways Paul instructs us to, especially due to the sheer amount of gadgets and

gizmos we have to distract us from one another these days: social media,

smartphones, tablets, and more.

I have to state right off the bat that this is a

very convicting subject for me, by which I mean that to be completely honest, I’m

not sure there is a way for me to give this sermon without being thoroughly

hypocritical. I love my iPhone and my

ThinkPad and my Twitter account and as for my iPad…well…look at what I’m

preaching from.

Taking lessons from me today is going to be a

little like taking pointers on how to fly from an ostrich, or accepting help

from a tobacco executive on how to quit smoking. This is very much the blind leading the

blind. But I do think this is a subject

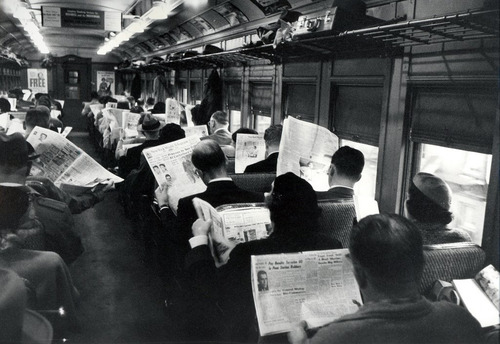

that is pressing for all generations because, if you’ll look behind me at the

PowerPoint image for this sermon, it’s a black-and-white photograph of an

old-timey public bus, chock full of people in every seat, and each of them,

rather than conversing with one another, has their newspaper open instead. Same basic concept, just a different decade.

So we all find things to distract us from each other,

okay. But it feels worse today than it

did 10 or 20 years ago, right? But

why? Shanae’s own words capture the “why”

quite well. She wrote to me:

Social

media, smart phones, and the internet in general are helping us produce

profiles with projected egos containing edited and filtered selfies and

providing us with a platform of show and tell.

“Hey, look

at what I ate today.”

“Hey, look

at my material things.”

“Hey, look

at how sweet my significant other is.”

And hey,

look at all of these misinformed prejudgments and opinions I have that spawn

unnecessary and heated debates among friends and sometimes causing families to

be divided. It has all become

complicated and distracting.

“You didn’t

text me back right away!”

“Why did

you like your ex-girlfriend’s status?!”

“Ebola is

an American epidemic!”

Just time

out. Let’s rewind.

When did

life become a competition?

When did

owning and being on the newest smartphone begin to matter more than helping

others, or spending quality time with the person right next to you?

More

importantly, why do loved ones have to compete for our attention?

In our need to be more connected with the wider

world, we have become disconnected from the closer world—the world of those

closest to us, like our families, like our loved ones, like, dare I say it, our

church. Paul says here to love each

other like members of our family, and, well, church *is* a family. So does that mean we have to treat everyone

like they disagree with us on casserole recipes?

Maybe today, but certainly not when Paul was

writing. Paul himself had no family to

speak of—he never married, never had any children—in a time when not having a

family was an absolutely lethal situation, especially when you grew old and

could no longer work. Today, we rely on

our pensions and Social Security and savings for our retirees’ livelihood; back

then, there was none of that. The

church, then, was Paul’s family in every sense of the word.

Treating people like family begins with seeing

people as family, which means you see them, warts and all. Your weird uncle with the off-putting sense

of humor. Your cousin with the wacky

survivalist political views. Or that guy

who swiped the baseball off of a little kid.

He’s somebody’s son too, probably somebody’s brother and cousin as well,

maybe somebody’s father.

Are you willing to see him as a whole

person? It’s harder to do that, I

know. We like our antagonists to be

cartoon villains. We like for them to be

easy to dislike, because not only are our minds already made up, but we also

tend to feel better disliking someone who is so, well, dislikable, because it

means it is their fault and not ours for disliking them.

What on earth does any of this have to do with

telecommunications and social media and the Internet? Well…isn’t it often easier for you to argue

with someone behind a phone, or a keyboard, or a computer than it is

face-to-face? Isn’t easier for us to

demonize the text or the voice than the whole person? Isn’t it sometimes tempting to be crueler and

meaner from a distance than close up?

Of course, Paul is hardly the model for

charitable Christian communication over long distances; after all, he’s the guy

who wrote to the Galatians saying—probably facetiously, but that’s the problem

with text messages, and it isn’t like Biblical Greek had emojis—that he wishes

those who were unsettling them over the question of circumcision would castrate

themselves (get it?). In this way, I

guess reading his words here in Romans makes me feel a little bit better about

giving this sermon: a good message can still potentially come from a

hypocritical messenger.

And that should be good news for each of us,

because that is what our own lives of faith and our own testaments to Christ

are: good messages from hypocritical and fragile messengers. We are all trying to live out the lessons of

a perfect Messiah in our broken and imperfect lives.

Perhaps the lasting impact of the Internet age is

that we are simply quicker at spreading our imperfectness to one another across

the earth. But it certainly does not

have to be that way. Because we are

still presented with a choice—and we always have been. A choice to look beyond the façade and past

the first impression and underneath the surface that so often our use of

technology only takes us. A choice to

plumb deep the depths of human character, with all of its foibles and quirks,

in search for that spark of divinity that God implanted in each of us as we

were being fearfully and wonderfully made in His hands.

A choice to engage with one another just long

enough and thoughtfully enough to see in one another the imago dei—the image of God—that we bear as living vessels. And so may we put down our papers, and turn

off our phones, and disconnect from the frenetic electronic pulse of the 21st

century, and then, with our eyes cast upwards, we shall see the face of

God.

May it be so. Amen.

Rev. Eric Atcheson

Longview, Washington

Longview, Washington

November 23, 2014

No comments:

Post a Comment